By Sidrah Roghay –

Kainat – raped in 2007 – is still waiting for justice and refuses to give up but her screams vanish in wilderness of criminal indifference

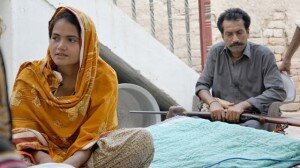

For international women’s day this year Kainaat Soomro addressed a hall brimming with people. As the 21-year-old rape victim talked about a documentary that narrated her quest for justice, her voice cracked with emotion.

Among the audience several people shifted uncomfortably in their seats — the film had received an international award and they felt it projected a poor image of Pakistan. Their reaction seeps down to the society which often views vocal rape victims like Kainaat with distrust. If reported, their cases either add to the long list of pending cases in the courts or in face of social pressures families withdraw in favour of the accused rapists.

There were 956 cases of rape and gang rape reported in the country in 2013, a 16.3 percent increase from the year before, states data compiled by the Aurat Foundation. Punjab topped the list with 846 rape cases reported since 2008, a 25 percent increase. Sindh reported 669 cases since 2008, but showed a 22 percent decrease when compared to the year 2012. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa reported 51 cases since 2008, with 9 cases reported in 2013, a 35 percent decrease. Balochistan had only 1 case reported in 2013.

In Faislabad which reported 200 rape cases in 2013, the highest in all districts, a shocking case emerged on September 12. A teenage girl was gang raped by five men. Three of the accused were sons of Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz MNA Mian Farooq, newspapers reported. In her first account, the girl admitted she could recognise all five of the accused. Four days later, her statement changed and she dropped all charges.

War Against Rape, a non-profit organization which helps victims, claims this is how most cases end. “Justice here is delayed. Victim families suffer social taboos. They feel no one will marry their daughters. Powerful accused rapists threaten them with consequences. Sixty percent withdraw their cases and settle for an out of court settlement,” said Rukhsana Siddiqui, a representative.

Mehnaz Rahman, Director Aurat Foundation agrees. “It takes a lot of guts to report a rape case considering the attitude of the police. Often rape cases take so long to reach conclusion because the first information report is filed wrong. Police are not willing to register a rape FIR and this tampers initial evidence, crucial when the case is presented in the court.” She claims this was exactly why Mukhtaran Mai was unable to receive justice even after her case was heard by the Supreme Court.

Mai, who has recently asked the Supreme Court to review her case, was gang raped in 2002 in tribal Baluchistan to settle scores between two tribes. After a struggle of eight years her case was heard in the Supreme Court, which acquitted all four but one of the accused—a decision which drew widespread criticism from rights activists.

Taking account of the dismal rate of the solution of rape cases in Pakistan, Kainat seems naïve to expect that she will get justice. “Every night before I go to sleep, I tell myself I will get justice tomorrow. It’s a routine I have been following for seven years,” says Kainat.

Dressed in her school uniform at her village in rural Sindh, Kainat was buying toys at a shop near her house. Four men forcibly picked her up, drugged her and took her into an empty wedding hall where they raped her. The year was 2007. The villagers asked her family to take the matter to the local jirga for an out-of-court settlement. Kainat’s father refused.

The jirga would declare Kainat a ‘kari’ and kill her for bringing dishonour to the family. Instead, he filed a case against the perpetrators who he claims are closely related to Liaquat Jatoi, former chief minister of Sindh and a feudal lord. To escape the threats which followed their decision, the family fled to Karachi. For three months they camped outside the Karachi Press Club demanding justice. They gathered a lot of media attention—rights groups followed, so did politicians.

As the case proceeded, Kainat’s brother was kidnapped and killed in 2009. Another brother had a murder case launched against him which the family claims is fabricated. There were attacks on their house and another on the city courts as the case proceeded. One of accused men claims that Kainat is his wife.

The Pakistani law does not recognise a marriage till the age of 18. When Kainat was raped, she was only 14. The high court gave its verdict in 2010. Due to lack of evidence, all four of the accused were acquitted – they were free men.

Away from home, the family has landed itself in a terrible financial mess. A respectable middle class family back at their village, today their sparsely furnished apartment in old Karachi is crying for attention. A mattress, three mismatched chairs, a stool which serves as a table, a broken computer and a metal cupboard occupy the room where she sits for her interview.

For Kainat and her family, life has become harder. The rights group which sent a tutor at her house to help her catch up on missed school years stopped doing so. To this day she lives under police protection. Her three brothers cannot find regular work as they fear for their lives. Health has taken a toll on her father who is recovering from heart surgery. Her sister works two shifts as a nurse at the Civil Hospital. Her income helps the house run its expenses. Kainat filed an appeal in the high court in 2012. It took two years for the case to finally begin. The accused would not answer the court summons and then they disappeared.

“The accused men have been found. The hearing now takes place at regular intervals,” says Faisal Siddiqui, Kainat’s lawyer. It could have been an open shut case had a DNA test been conducted after the rape took place. “The test is expensive and there is only one lab in Islamabad. Without a DNA test these cases become complicated. At this rate Kainat’s case is actually making significant progress,” notes Siddiqui. Will she find justice? “It’s hard to say,” Kainat’s lawyer replies.

Kainaat refuses to give up. “I have suffered so much. Why should I give up before I get justice?”