By Haseeb Asif –

A ‘Revolution’ decades in the making

In 1978, a young and ambitious lawyer from an unremarkable family in Jhang, moved to Lahore to work as a lecturer at Punjab University. In 1981, he established the Minhaj-ul-Quran organization. In 1986, he received a PhD in Islamic Law from the university where he was teaching. In 1987 he inaugurated the official headquarters for the Minhaj-ul-Quran International at a palatial building in the upscale area of Model Town, Lahore. By 1989, he had established his own political party, Pakistan Awami Tehreek and had announced his intentions to contest the 1990 elections.

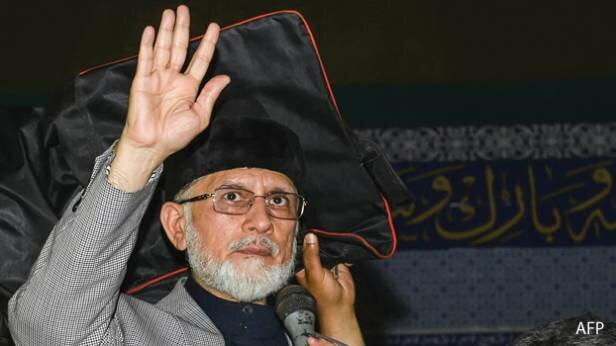

Tahir-ul-Qadri was as much a mystery then as he is now. People were confused and asked the same questions, where had this man suddenly come from? Who funded the millions of rupees for setting up his stronghold in Lahore? Who paid for his foreign trips? Where would the money for his election campaign come from?

Many of these answers can be found in the circumstances this man grew out of and his talent for acquiring powerful patronage.

If his school of Islam is ostensibly Barelvi with vocal sympathy for Shia history and thought, it’s because Qadri was trying to make a name for himself in an era of deep rooted sectarianism, in a district, Jhang, where Sunni extremists were rampant on the streets, and where the Shia elite were looking to invest in moderate Sunni scholars and thinkers.

In 1987, the Sufi Saint from Iraq, Tahir Allauddin, attended the inauguration of the Minhaj-ul-Quran building. In 1988, at a Minhaj-ul-Quran International conference in London, Mian Nawaz Sharif gave the keynote address, where he claimed to be a ‘personal devotee of Dr. Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri’. The young Nawaz specifically said in the speech that Qadri’s Model Town stronghold had nothing to do with the Sharifs, but popular belief at the time held firm that the land was a gift from a patron to his (potential) client.

Qadri lost the 1990 elections quite badly, while monetary patronage on religious grounds was overflowing, political patronage wasn’t as forthcoming. In 1991 he made an alliance with Tehreek-e-Jafria, but Shia-Sunni unity didn’t raise his political profile anymore than a further alliance with a Salafi organization did. The country simply wasn’t voting in religious personalities.

During the ensuing decade, Qadri would publicly quit and rejoin politics many times, his organization started flourishing abroad, money and Mureeds kept flowing in, he authored books, he became an expert on Fiqh, he started growing bolder with the choice of location for his Millads, and at one such gathering at the Mochi Gate Lahore, he first spoke of Inquilaab and how he had seen prophetic dreams and angels telling him that he, Tahir-ul-Qadri, would be the one to lead the revolution that would set this country right.

Then came Musharraf and enlightened moderation, and Qadri made himself readily available. After the martial law, and for the first time in his life, Tahir-ul-Qadri narrowly won a seat in the National Assembly, in the somewhat farcical elections of 2002. But like other politicians who had jumped on the General’s bandwagon in the early days after the coup, Qadri soon realized that a rubber-stamped parliament could only do so much for his political ambitions, and tendered a resignation in 2004.

Then he disappeared. For almost a decade he remained abroad, networking, finding donors, randomly appearing at peace conferences, inter-faith unity events, he wrote more books, even a 600 word Fatwa on why suicide bombing was Haraam, it got him international press, he consolidated by opening even more Minhaj centers around the world; meanwhile at home, his Minhaj-ul-Quran mosque and seminary had now become Minhaj University, with a large student strength that would later double up as his foot soldiers in his various rallies, protests and marches.

He settled in Canada, and many took to calling him Shaykh-ul-Islam Dr. Tahir-ul-Qadri Canadvi. Then, as suddenly has he had first arrived on the scene all those years ago, he announced, in 2012, that he was coming back to the country to lead that glorious revolution which he had once promised.

He led a long march. He sat in a container. He made fiery speeches. He harassed the democratically elected incumbent government, and two years later he’s at it again. Who are the patrons this time? Rumours suggest a khaki tint, but we’ll find out in due time.

This lukewarm revolution has been decades in the making. A cleric with a serious messiah complex, nobody can be more ambitious. The only question we can ask is, what took him so long?