By A. Rahim Khan –

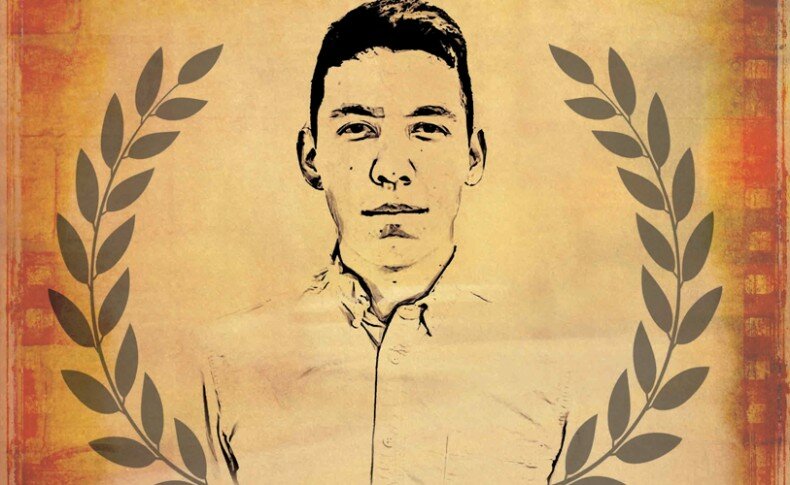

A Pakistani at Cannes

The steady stream of Hollywood and Bollywood into our cinemas, while most welcome after all these years, tends to give rise to cinephiles. Yes, everyone loves a yarn or two but for more serious cinema, we must look elsewhere they say, to the Continent, we are told. World cinema, independent film, art house or avant garde, these are the apparent markers of cinema as art and for their showcase, many film festivals yearly occur around the world.

Foremost among these events is the Cannes Film Festival held every May, set against the azure waters of the French Riviera where cinema’s greats have often come to premiere their films, and the industry to catch a bead on the next best thing. Pakistan’s attendance at the film festival has been short of encouraging but in recent years smaller, more independent films have been screened and at this year’s Cannes, director Hamza Bangash’s short film, Badal, was selected for the Short Film Corner program.

At only 23, Bangash has already had a career in theatre, putting up a couple of productions in his hometown of Karachi, later venturing into documentary and filmmaking after studying in Canada. In this month’s Pique, the up and coming director speaks about his experience at Cannes, his theatre years and why we need to stop comparing local cinema with that of India’s.

Having been so involved in theater, do you think it’s come into its own, considering the successes of such plays as Pawnay 14 August, Grease etc?

Film and theatre in Karachi is as vibrant as it’s ever been. I remember when I was starting out Nida Butt had just run her first staging of Chicago and people were waking up to how exciting theatre has the potential of being.

Having had the opportunity to watch Pawnay 14 August, and worked closely with Mustafa Changezi of ‘Grease’ fame on Badal – I can wholeheartedly say there’s been a resurgence of theatre in Karachi. However, I’ve always been a supporter of art that makes a difference – and in that light I feel that the current theatre scene owes a lot of its’ success to the ground-work done by Sheema Kermani and her dance/theatre group Tehrik-e-Niswan and could still learn a lot from their commitment to community involvement.

How was your own experience in theatre, considering that you started out quite early?

My experience with theatre in Karachi was fantastic and regrettably short- lived. At 17, I wrote, directed and produced a short piece called Rise that tackled the Marriott bomb blast and political inactivism. The next year, my theatre group moved into the Art’s Council for our staging of Arthur Millers The Crucible- a play about the impact of religious fundamentalism on a conservative society. I loved working in theatre as it was where I made most of the connections that carried on into film, introduced me to the arts scene in Karachi and allowed me to explore the topics that would grow to be my passion.

You’ve segued from theatre into film, what has the transition been like?

Difficult. The immediacy of feedback that you receive in theatre is something that you’re hard-pressed to find in film. You can work on a project for months and never know how it will be received. Also, you have to change the way you represent your ideas. In theatre, because of staging limitations you’re forced to be abstract in representation- but with film the audience expects 100% reality. Delivering that- and staying true to the abstract themes that I want to show in my films- has been a challenge.

Independent cinema seems to be leading the charge in putting Pakistani film back on the map, why do you think this is? And why do you think mainstream cinema is lagging behind?

In any situation where there is a lack of government support, Independent cinema will lead the way. Combine that with a volatile political situation where the arts are far from the first priority, or worse, ignored and vilified by the powers that be, you end up with artists who take matters into their own hands. I believe mainstream Pakistani Cinema will catch up soon – now that they realize the audience is there – and that people are willing to spend money on home-grown, Pakistani content.

With this so-called ‘revival’ of film in Pakistan, what do you think we can expect from the industry in the future?I think you can

expect the seeds of a film infrastructure. Filmmaking is an activity that demands so many different kinds of skilled workers – and for people to really collaborate to succeed. And as Pakistani filmmakers grow, so will the need for greater collaboration, resulting in artists across different mediums banding together to create something bigger than themselves. It’s already happening with the creation of the Pakistani Academy Selection Committee and the upcoming release of Nabeel Qureshi’s Na Maloom Afraad.

What was your reaction when ‘Badal’ was selected for this year’s Cannes Film Festival? What was the experience like?

I was thrilled. Badal is my first attempt at narrative filmmaking and a story really close to my heart. The experience was otherworldly, transforming. I had the opportunity to mix with the best and brightest in the industry, and it has very much shaped my direction as a filmmaker ever since.

Over the years, India has developed a very strong presence at Cannes, do you think it’s possible for Pakistani film to develop such a standing?

I think Pakistani’s really should stop comparing ourselves to Indian cinema. Indian cinema has had government and national support for over fifty years, and now is a global force to be reckoned with. Indian studios are inking deals with the best of Hollywood talent. Pakistan is just getting started again, after having a rough 30 years. It’ll take time, but we’ll grow. We always do.

Karachi tends to figure a great deal in your work, are these love letters to the city?

It’s a city that holds a special place in my heart. It can be both fascinating and impossible, and I’ve yet to have the privilege of living in a city that is even half as invigorating as Karachi.

Having already done short form for both film (Badal) and documentary (Smile for Karachi), do you plan to branch out into more feature length ventures?

Definitely.

What’s next for Hamza Bangash?

I can’t tell you just yet. I have a big project in the pipeline that’s a collaboration with a well known Pakistani artist and something I’ve wanted to do for a while. It’s going to be a big year.

The writer is a journalist based in Islamabad