By Haseeb Asif and Irfan Bukhari –

Dissolving the writ of the state

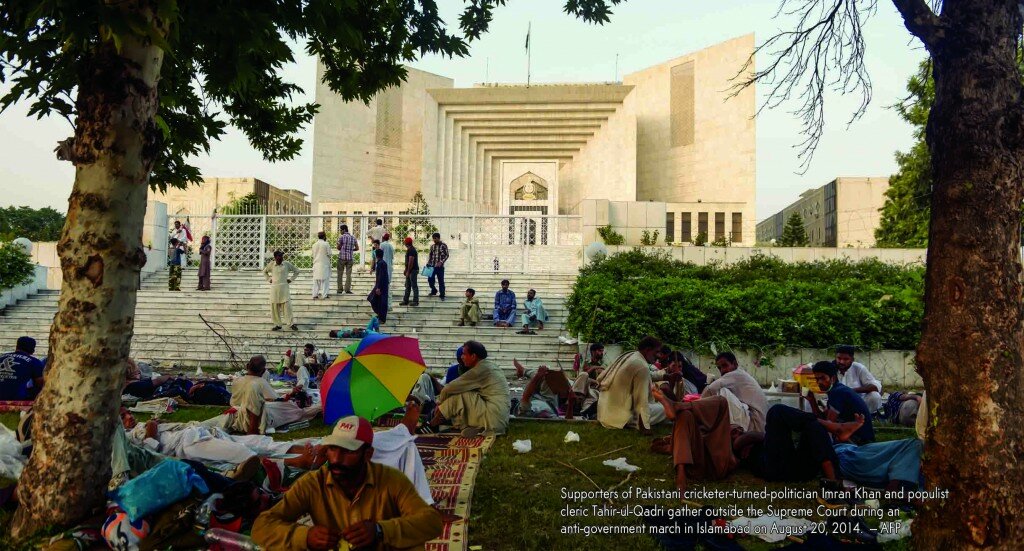

The twin marches fiasco has left the country reeling. A battle of Lahore, touted as a battle of Punjab, shifted to the federal capital this August and while protesters staged sit-ins outside the parliament, the administrative and bureaucratic functioning of the state ground to a resounding halt.

The economic losses are in the billions. Foreign visitations have been cancelled. As rains and flood gripped the urban and rural centers of the country, politicians sat helplessly besieged by Imran Khan, Tahir-ul-Qadri and their own incompetence.

There were many angles, many ins and outs. The media coverage has been relentless, almost to the point of exhaustion, scores of articles and opinion pieces were written in print, but the confusion over what was actually playing out in Islamabad remains unresolved. At the point of writing this, the drama is yet to reach a climax.

Regardless of where it goes from here, there will be long lasting consequences. Every political action has an unequal and exponentially worse reaction. In the following pages, Pique looks at some of the more troubling aspects of the protests and the government’s stuttering, stumbling response. We will also take a look at some of the major and minor players in this theater.

They say it’s all been scripted, staged, and as befits any great story, we pay homage to some of the minor and major players, and try to figure out who’s been taking cues from where. Some of the ‘revolutionaries’ appear in special profile boxes in accompaniment to the story. They who have been struggling from inside their air conditioned SUVs.

It is very symptomatic of the malaise this country’s politics suffers from that the rich battle the rich in the name of the poor, hijacking otherwise meaningful socialist agendas, and interfering with genuine, even if currently belligerent, political parties, like the PTI. But regardless of these jesters, and regardless of how this crisis is eventually resolved, there are a few sobering conclusions and realizations, almost all of them disheartening, that we can already take from the events of last month.

A circle of fools

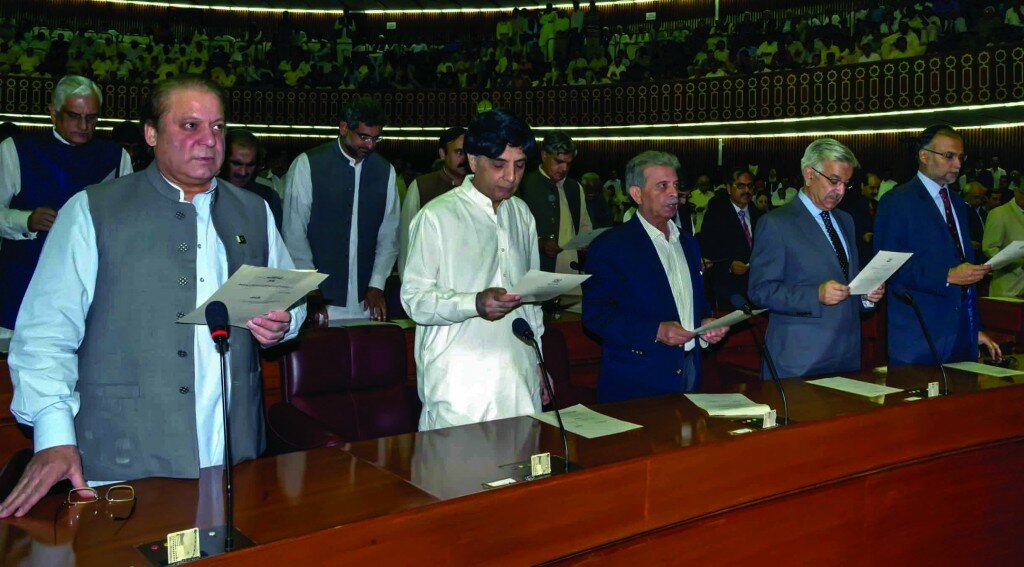

There can be little doubt that this entire episode of street agitation has been badly mishandled by the government. A government that could still claim, despite wild accusations thrown around by Imran Khan, to have a heavy mandate of the people of Pakistan, years of experience in affairs of the state, and a supportive judiciary and in-house opposition. The latter two were a big problem for Nawaz Sharif in the late 90s.

Unfortunately, nothing has changed since then. Surrounded by the same old faces that have lead Nawaz down perilous paths before, his personally assembled team of aides and advisors, his cabinet, his senior most ministers, all proved themselves grossly incompetent, letting him down once again. Years from now, when people will look at this chapter of history, the siege of Islamabad in August 2014, they will mostly sit and scratch their heads and wonder how so many bad decisions were taken at the behest of the ‘cream’ of the PMLN.

Everybody from the model of incompetence Chaudhry Nisar, the interior minister in absentia, to the thuggish travails through the law ministry of Rana Sanaullah, have left Nawaz the weakest, perhaps most humiliated Prime Minister in Pakistan’s history. It is one thing to be ousted by a military takeover, which, while leaves leaders powerless, also makes political martyrs out of them. It is quite another thing to be so completely undone in front of the watching world, by street protests turned into a national crisis by a sycophantic but tactless team of advisors.

For over a year this advisory council told Nawaz to ignore Imran Khan’s demands to open four constituencies. Yes, legally there wasn’t much the government could have done. The matter was entirely up to the election tribunals, but politics is about assuaging your opponents. Peace offerings could’ve been made, as they were made in desperation in early August. Some nominal judicial commission would’ve acted as a gesture of goodwill. Guarantees could’ve been given. They weren’t.

Fast forward to this summer and the same people who had advised inaction for so long, sent the administration into panic mode. 14 people died in Lahore, Rana Sanaullah was personally culpable, giving the kind of legitimacy to these twin marches that no amount of rigging allegations could ever have done. The inquiry commission was too late with its report, the FIR registered was considered a farce by the complainants, the scenes accompanying the incident, a man called Gullu Butt smashing vehicles in front of the Minhaj-ul-Quran, give birth to a new lexicon of anti-PMLN sentiment.

Then the crowds came to Islamabad, the government once again failed to ensure its safety, there was an altercation at Gujranwala, the government also dithered around in its security policy at the capital. Confusion abounded as to what routes would be left open, where the containers would be put, where the protests would be allowed and who was in charge of the security of the sensitive red zone.

Article 245 was invoked to much criticism in media circles. The army was involved in the negotiation process as a guarantor to even more criticism. For almost two weeks nothing was done about the insulting, inflammatory and anti-state speeches delivered at the parliament’s doorstep, then once again panic and retaliation from an untrained, unprepared, and unarmed police force ensued. Article 245 lay dormant as the army stood by and watched.

Chaudhry Nisar was at the forefront of the official strategizing. He followed up every misstep with a long, dull speech. He gave Nawaz the gift of being referred to as a liar on the floor of the parliament house. He gave sureties that never materialized, despite being the only PMLN leader to have missed no opportunity in meeting the protesting parliamentarians, opposition leaders and army generals in private. In public, his personal vendettas cost the PMLN more embarrassment while he reveled in the media face time.

Other people close to Nawaz weren’t far behind in this quest for personal relevancy. Khawaja Saad Rafique made sure he was seen parading around the streets of the red zone, reprimanding police for manhandling media workers, an admirable intervention on its own, but what exactly was he doing here? In what capacity was the Railway Minister actin`g as an overseer of riot control and the restoration of peace? Especially when said Railway Minister’s election constituency was one of the most controversial among the ballot stealing charges.

These people have ruined Nawaz. He is set to become the first PM in this country’s short history to lose all power and authority without the military issuing those dreaded mutinous orders. There is still one last chance of course. There is still some time. The military has so far resisted the urge to intervene. His personally appointed army chief has given him a lifeline, but he simply must discard the prevailing echelons of PMLN leadership and reshuffle his team, or else he is doomed.

Boots on the ground

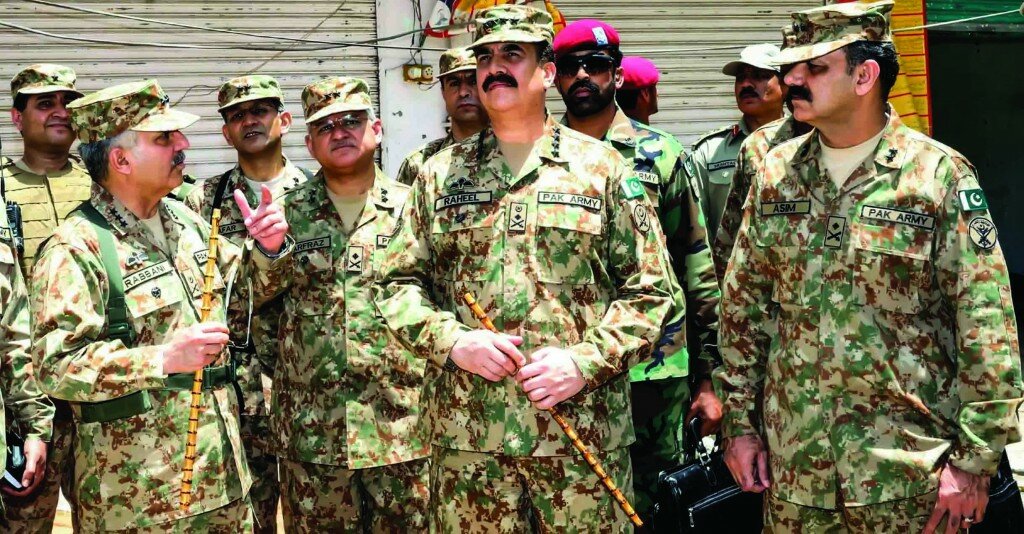

On that note, the positive role of the Chief of Army Staff Raheel Sharif deserves some praise. Reports now tell us that 5 of his 11 Corps Commanders, also incidentally the 5 outgoing Generals in October, were in favour of direct military intervention. But Chief Raheel personally shot down these suggestions, there was even mention of courts-martial, if anything took place without official sanction, behind the scenes.

Much criticism has been leveled in social media and on television channels about past military adventurism, about hard coups and soft coups, and about the backdoor interference in political matters by rogue Generals. While the latter is true in this scenario as well, and it’s also true that civil-military relations have undergone a major shift during this crisis (the military has won back some desired foreign policy initiatives), the blame can’t all be appropriated towards the army. Not this time. Credit should be given where credit is due. It seems that Nawaz’s much criticized policy of hand picking and promoting Generals to the COAS position might not be a policy eternally fated to fail, as people thought.

This positivity comes from the military, despite the fact that some of Nawaz’s senior ministers have launched vindictive assaults on the khakis and even slung some mud at the COAS himself. Whatever the reasons, the fact that the chief gave a clear signal in favour of a political resolution to the crisis, and against direct intervention, is something to be grateful for. A precedence of restraint perhaps, to be set down for future chiefs as well, and also welcome news that the army is not a single-minded monolith as branded in analytical criticisms. It does have a system of internal dialog. Which might not be greeted with enthusiasm by proponents of a staunch and unified military mindset, but for the martial plagued politics of Pakistan, it’s a welcome relief.

However, avoiding past indiscretions doesn’t mean the military’s role has been entirely positive, or that it has taken its rightful place under command of civilian leadership. Under the aforementioned article 245 of the constitution, the security of the red zone was made the obligation of Pakistan’s armed forces. But there are pictures showing that they stood by and watched while non-lethally armed civilian police tried to disperse and tackle the rioting crowd.

What the unarmed police couldn’t achieve in two weeks, the lethally armed military could’ve achieved in a matter of minutes. It chose not to. That isn’t entirely an apolitical decision, and it contravenes the civil-military chain of command. This isn’t something new, a similar thing happened in 1977, when Bhutto ordered the military to disperse the thickening mob. His orders were never carried out, and we all know what came after. Small mercies from the boys in khaki, yes, but still a long way to go before any concrete shift in the power relations between civilian and armed personnel.

Enforcing the writ of the state

Most worryingly, the protests exposed severe weaknesses in the state’s institutions. Before the advent of the long march, the Lahore High Court decision saying that the march should be kept within constitutional and legal parameters was entirely neglected by Imran Khan and Tahir-ul-Qadri. The Punjab government too failed to remove containers and impediments from the roads despite LHC directions. The orders of the apex court demanding the immediate vacation by the protesters of the Constitutional Avenue also fell on deaf ears.

But perhaps more than the courts, the institution which had to pay the heaviest cost for the mistakes of the politicians and the inaction of the military, was the civilian law enforcement.

Police training and recruitment was badly exposed. The world now knows that they can’t deal with crowds, they have little clue about riot control, they don’t excel in non-lethal force, and that they are the first ones sacrificed and the last ones saved. The morale of the police at this point in time is dire. At an all time low.

The last few weeks saw panic appointments and transfers of senior officers who didn’t want to commit to the government’s orders because of a fear of being left high and dry afterwards, and being abandoned to reprimands and media criticisms. The issue is complex. Civilian law enforcement has never enjoyed the same privileges and independent agency as the armed forces. When Musharraf ordered the operation on Laal Masjid, girls with sticks were declared enemies of the state. It was called a perilous situation, in the heart of the federal capital, so close to the corridors of power.

But what happens when a civilian government tries to enforce the writ of the state? Stick wielding, police beating, parliament-defiling mobs aren’t exactly friends of the state. They too camped at the heart of the federal capital, they weren’t here on a picnic. Is threatening to take over the civilian corridors of power not sedition? Why then, was the police figuratively castrated, unarmed, and unable to exercise its constitutional monopoly on violence and detention? Is that just a privilege for the khakis?

This mob was armed with rocks and sticks and rhetoric about revolutions and independence. The next one might be armed with violent intolerance for all non-subscribers to a certain ideology. Is the state expected to surrender to any unruly crowd gathered at its footsteps?How can a state that can’t deal with internal threats to its authority be expected to deal with the external phantasms our security experts assail us with? What message does this send out to the Islamic militants entrenched in our Western borders? That Maulana Fazlullah took this opportunity to release a nugget to the press speaks volumes about this exposure of law enforcement inadequacies. He simply stated, that if 30,000 people can paralyze the state in a matter of a week, imagine what we could do.

Amir Rana, Director PIPS says that the PTI and PAT protest movement exposed the police in a manner which left it more demoralized than ever before. “It is not good for the writ of the state, it is in such scenarios that militant organizations like ISIS get the ambition to try and capture the state.”

Yes, 14 people died in the Model Town tragedy, when the police was afforded live ammunition. There will be inquiries and investigations, and the responsible officers will be punished. But illegitimate use of force doesn’t mean the police should be stripped of its legitimate use of force.

There are a hundred times that number missing and dead in Balochistan. Can FIRs be registered against the intelligence agency that people claim is the offender? Where are the long marches for that? A certain Mama Qadeer did make his long march from Balochistan to Islamabad. Without cavalcades, without containers, without the luxury of expensive sound systems and rich financiers. He was sent back empty-handed.

The point is to build a system of justice where every person and institution can be held accountable, holding only politicians or civilian institutions accountable achieves little justice, but much institutional weakness to be preyed upon by detractors and usurpers. The armed forces will retreat back into their garrisons once the long marches are over, safe from criticism, back under an opaque, inaccessible system. Who will then enforce the writ of the state on the streets? This humiliated, demoralized police?

There are wounded and injured policemen lying in PIMS who are being called brutes and thugs on television, and they are yet to even receive an official visit by their superiors, their commanding statesmen, who will join in on the police bashing, while these low salaried individuals recuperate and get ready for another day of being pelted with rocks and bricks.

On the other hand, valid criticism must also be meted out. The failure of the law and order situation in Islamabad is also the failure of Punjab Police. Why did PMLN’s own strong-men, the officers they have been appointing and promoting for 6 years, keep backing out at the crucial hour? They had to change two IGs during this crisis, firstly their own man Aftab Cheema, and then Khalid Khattak, both failed to carry out the government’s wishes.

It’s a failure of the entire PMLN backed Punjabi establishment. No officer was willing to come forward. In the end they had to rely on Tahir Alam, the blue eyed boy and personal enforcer of Asif Ali Zardari and Faryal Talpur.

There is a lesson for Shahbaz Sharif here. The delegation of authority. While his rolled up sleeves and stomping around the yard activities look good for the cameras, they don’t institutionalize competence or put things on a self-correcting and progressive track. If he keeps accomplishing everything through personal interference then his interference will always be required, and nothing will get done by provincial organizations themselves. Shahbaz’s gonzo approach to being CM has eroded the autonomy of many of Punjab’s functional institutions, and have exasperated the problems of the dysfunctional ones.

Shahbaz wasn’t there to order his elite force around in Islamabad. He wasn’t there to order encounters. And therefore the Punjab police did what the lack of chain of command compelled it to do, nothing. Inaction is the only thing the much vaunted Punjab Police has brought to the capital.

Legal lacunae

All this discussion of law enforcement tactics and shortcomings doesn’t preclude, of course, the fact that the government should’ve armed them with legal restraints, if not physical ones. Ever since they announced a stick wielding march on the prohibited red zone, all of these protesters should’ve been charged and indicted on the following non-bailable offences. Section 7 of the Anti-Terrorism Act and the Pakistan Penal Code’s section 124-A: sedition. PPC 149: unlawful assembly. PPC 186: obstructing public servant in discharge of public functions. PPC 153: wantonly giving provocation with intent to cause riot.Early legal measures, which were entirely under the ambit of the constitution, would’ve given the police teeth to bite with and clamped down on the miscreants before they sparked the chaos and anarchy that left 3 dead and over 400 injured.

But the state dallied, as ever. And things went from bad to worse. When the government finally did issue warrants and started registering cases, about 200 people were picked up from the Constitutional Avenue and various hospitals. A further unpopular move, after the storm had already wrecked the harbour.

And even then the state failed to enact any consistency in its directives. These cases have been put up as part of the negotiation process to be dropped. The people charged will be let go, the offences stricken from all records, in exchange for easing up on some of the more immediate pressures on the government.

While the cases can indeed legally be withdrawn by the nominated complainants – in this case the government of Pakistan – and presidential pardons can be given in cases that have already been decided – in speedier anti-terror courts for instance – for offences as high as treason, this does create a big problem in a certain ongoing high profile trial.

Part of the pressure on Nawaz Sharif’s government has been over the decision to go forward with General Pervez Musharraf’s trial for high treason, over the abrogation and holding in abeyance of the constitution. The forces who have been pressuring the government to let the dictator flee the country, and the General’s own legal team, can now point to these sedition charges being dropped like a hat in the wind, and ask for an equally politicized deal.

The problem here is that while the law empowers the people occupying these seats of authority to take these measures, these measures serve in only undermining that authority. While Nawaz Sharif can ease political pressure on himself by withdrawing sedition charges against Qadri and Khan, while also granting clemency to Musharraf, the consistency, integrity and authority of the seat of the Prime Minister of Pakistan, supposedly the chief executive of the state, is thrown into question.

Precedents become legal and administrative shackles, the PM following Nawaz will be bound, in some ways, by the decisions he takes and precedents he sets today. This would be doing a great disservice to the office of the PM, not to mention the fact that in both the rioting in Islamabad, and the Musharraf treason case, while the primary complainant might be the government, it is not the only aggrieved party. It would be grossly unfair to the institutions defiled and chains of civilian authority brought into disrepute by the actions of these men, to never get the opportunity to be vindicated and see their defilers tried in a court of law.

Sitting on the fence

The role of the opposition parties too, has been indecisive. On the one hand they claim to support the democratic mandate won by the PMLN and the constitutional right to finish their tenure. But they stand for institutional integrity only on a ‘for official consumption’ levels. Their members and workers, in media appearances and out of parliament meetings, have either supported the cause of the protesters, struck blows to a reeling government, or just plain sat on the fence over vital matters of civil-military relations.

While Zardari meets with Nawaz and offers advice on taking a soft stance and finding political solutions to the crisis, Qamar Zaman Qaira appears on television channels everyday denouncing the government and trying to legitimize the claims of Qadri and Imran. Altaf Hussain comes on air one day speaking against the protesters, and the next day speaking against the government. Aitzaz Ahsan stands in the parliament venting personal invective against the incumbent party, while outside the assembly he offers vocal support for the prevailing democratic order.

This is the finest political opportunism. Trying to resuscitate their political fortunes while teetering on the edge of the civil-military divide, pushing the people but trying not to tip the system over the edge, let’s not forget who were the biggest losers in Punjab compared to the previous ballot, the fact that the four constituencies that Khan has so vociferously demanded investigations into were also the four worse defeats for the PPP in Punjab is no coincidence, neither is the fact that Aitzaz Ahsan’s wife suffered a humiliating defeat in Lahore after which she had to forfeit her security.

Every crisis provides opportunities for political point scoring, and this one has proven no different. Even Rehman Malik has found a way to become relevant again. That the PMLN couldn’t find a better mediator in their own ranks, someone who could go and convince Qadri and Imran to come back to the negotiating table, is a lamentable fact in its own right.

But still, the fact remains that a united democratic front, even if only for show, is still a departure from the traditional backbiting politics that elected parliaments have been host to. After all, internal disunity is what primarily invites military adventurism, that and a non-committal Supreme Court, when it comes to defending the civilian government bodies.

So there were positives. A number of resolutions were passed by the parliament for the supremacy of the constitution on the suggestion of Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) when the joint session of the parliament was summoned, in early September, to discuss the political turmoil.

Members and organizations of the civil society along with bar and traders associations also vowed to resist any attempted derailment of the democratic order in the country. The antagonistic parties – PTI, PAT and PMLQ – blamed the incumbent and opposition parties for uniting to protect their privileges and maintain the status quo, which quite frankly, was farcically ironic on the part of the PMLQ, and somewhat ironic on the part of Sheikh Rasheed supported PTI. Imran Khan also alleged that the lawyers’ fraternity which was opposing his sit-in had in fact been bribed by the PMLN. This was just another in the swathe of unfounded allegations Khan shouted out from atop his container during the course of August.

The Oxford-educated chairman of PTI used repulsive language against his opponents and the same line was faithfully adopted by his party’s trolls on social media and on the streets. Imran Khan without sharing any concrete proof leveled serious charges against politicians, journalists, lawyers and everyone who dared criticize his political strategy of crossing red lines. One would think, a former CJP won’t be alone in filing a defamation suit against the former cricketer, come the end of the month.

Vultures in the media

The political crisis not only unveiled the dirty faces of a few politicians and opportunists, but also unraveled the irresponsible attitude of Pakistan’s major media houses, particularly the electronic media that was consumed in an unethical rat race to be the first to break, often unverified, news. The complete lack of authenticity in the news verification process, and the unbridled biases and prejudices media houses like ARY and Geo wore on their sleeves, was a form of information aggression against the citizens of this country.

The former news channel was maligning the government and the parliament while the latter was coming down hard on the PTI and PAT leadership. The former was defending the military establishment and denying rumors of any script behind the protests, while the latter was hell bent on establishing that the whole episode was written in some dark, smoky corner of the GHQ. They say ratings don’t last, good journalism does. Clearly, Pakistan’s two leading television channels didn’t get the memo.

The abandonment of journalistic standards landed the lowly media workers, reporters, camera crew, into trouble while the senior officials raked in the numbers. Journalists representing Geo and Aaj were thrashed by furious PTI workers. While ARY complained that the police manhandled their staff.

A vitriolic call for banning Geo was also run on social media which further deteriorated the situation. Sympathizers of the PTI and PAT launched a vilification campaign online where unsubstantiated claims were made regarding some journalists taking huge bribes from the PMLN leadership.

Rasul Bakhsh Rais, Director General Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad (ISSI) said that the media was in no small part responsible for the prolonged national agony. “Live coverage given to PTI and PAT by TV channels complicated the situation, some of these anchors have no professional values, the government is also weak right now and cannot touch them,” he added.

Rasul Bakhsh Rais, Director General Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad (ISSI) said that the media was in no small part responsible for the prolonged national agony. “Live coverage given to PTI and PAT by TV channels complicated the situation, some of these anchors have no professional values, the government is also weak right now and cannot touch them,” he added.

Sects and violence

In a nation strangled by so much sectarian hatred, politicizing a sect is always a sensitive matter, prone to creating more problems than it solves. While some analysts, both here and abroad, were lauding Tahir-ul-Qadri for putting together the Sunni Barelvi school of thought under a political banner, and allying with a Shia political movement, the Majlis-e-Wahdat-e-Muslimeen (MWM), the outcome of their long march on the capital and subsequent assailment of the incumbent government provided a window for the traditionally hardline Sunni Deobandi groups, like the Jamaat-e-Islami, to present a softer, more politically astute and state friendly position forward.

Moreover, as a reaction to this alliance, hardliner Deobandi groups like Ahl-e-Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ) headed by Ahmed Ludhinavi took to the streets to express solidarity with the PMLN led government. The ASWJ taking out a rally against ‘elements attacking the state’ is a farcical position in reality, but good press goes a longer way than rotten histories, and they were able to attract positive face time in the pro-state circles of the press.

A senator, one Sajid Mir of the Markazi Jamiat Ahl-e-Hadith, was able to make a statement in the parliament that Tahir-ul-Qadri was defaming religion by employing his self-interested, political interpretations. There was no sense of irony here, these words being uttered by someone who’s made a political career doing the same. But the assembly thumped their desks and people watching on television murmured in faint agreements.

Commenting on Qadri’s religious revolution, Muhammad Amir Rana, Director Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS) said that some smaller sectarian groups like MWM and Sunni Ittehad Council were using his platform to enter mainstream politics of the country on strictly sectarian lines. “There was an impression in the west that this alliance will develop a counter narrative against militancy and terrorism in the country but I disagree with it,” he added.

All Tahir-ul-Qadri has succeeded in doing is pushing the government back towards the Deobandi organizations, who will reap what he has so tactlessly sown.

It wasn’t long ago that the state was clamping down on hardline Sunni groups. When Sufi Muhammad made his anti-state declarations in Swat, he was afforded no reprise, the state came down on him with immediate force, they arrested him and his closest aides, who were all charged with sedition.

That Tahir-ul-Qadri can stand in front of the parliament and make his own seditious claims says two things, that the state has been forgiving of Barelvi Islamic groups, as a counter to the Deobandis and Salafis, and that this tacit support has been reciprocated with belligerence; it was after all, a Qadri, a Barelvi, who shot Governor Salman Taseer. What these often persecuted and unorganized Barelvi groups are doing under the ambit of Tahir-ul-Qadri’s crusade against the civilian state, is essentially driving their persecutors back into state patronage.

His crusade is also questionable itself. PMLN leaders claim that Qadri was holding his disciples hostage, they were forced to attend his charade in exchange for monetary compensation and food. Many of his protesting army are workers and graduates of his Minhaj-ul-Quran madrassas and university. Some are economically dependent upon his good graces, others think of him more as a Pir than a political revolutionary, following his orders on blind faith rather than a real conviction in his arguments.

An abandoned province

Last of the major players, but not least, Imran Khan. His political ambitions and myopic focus on the federal centre has left the province he won in the elections, the province where he has formed a government and appointed ministers, absolutely reeling. People have long remarked that Imran Khan risks losing Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in his bid for federal power, but the real tragedy is, that Imran knows this. He knows this, and is willing to make that sacrifice. He was never interested in ruling KP, in working at a provincial level for five years, in building a results based reputation.

His rhetoric based street politics is all he has, and the fact that he has resorted back to rallies and public speeches a year after the elections, despite leading the second most successful party in those elections, serves to demonstrate that he’s not a parliamentarian. He doesn’t have the patience for it. He can’t bide his time, and play the politics of the benches. He wants it all at once, and the only way he thinks he can get it, is by sitting outside the parliament, not in.

Nevertheless, this commitment of his to the politics of agitation isn’t shared by all of his party members, followers or voters. Disillusionment with the PTI-led coalition government in KP is spreading. The provincial government became almost paralyzed because Chief Minister Pervez Khattak was camping in Islamabad along with his ministers as they were required to participate in the PTI’s protest sit-in and ensure a good attendance of workers. The CM drew flak for his absence from Peshawar when the city was struck twice by devastating rainstorms that killed up to 30 persons and destroyed houses.

There was also the growing rebellion on the issue of resignations from the assemblies. A group of dissidents, all of them hailing from KP, refused the contentious decision taken by Imran Khan. Former bureaucrat Gulzar Khan, elected MNA from rural Peshawar, headed the group that, by last count, had six confirmed members, which was expected to grow once the Speaker of the National Assembly invites them to personally verify their intentions to resign.

In fact, the urge to save the KP provincial assembly brought together the normally fractious opposition parties to initiate the no-confidence motion against CM Khattak, as the move constitutionally bound his hands from dissolving it. The provincial assembly cannot be dissolved by a CM undergoing such scrutiny in the assembly. Critics even claimed that Khattak himself gave the nod to this preemptive strike as he was personally opposed to Imran Khan’s directive as well.

But assembly stand-offs aren’t the only blowbacks from the Islamabad sit-ins. Parvez Khattak had to offer a refusal to meet Chinese officials as part of the ongoing standoff with the government. As we now know, the entire foreign tour was cancelled on account of the seemingly never ending protests. Something that can cause immense investment vacuums in both Pakistan and KP.

The minister for education in KP, Atif Khan, has been left frustrated over projects he wanted to initiate, as he has been busy making arrangements and bringing people to the Islamabad sit-ins. MNA Musarat Ahmed Zeb, one of the dissenting voices from the KP assembly, was on Geo’s Capital Talk in early September, bemoaning the abandonment of bills and vital policy matters in the KP assemblies over the focus on the Azadi March. She has since publicly refused to sign any resignation out of protest, and also attended the National Assembly session voicing her decisions to stand by the democratic institutions of the country.

But while KP suffers, ministers called by Imran enjoy privileged stays at the completely booked KP-House in Islamabad. While the more affluent members of PTI, like Jehangir Tareen, have been seeing out the tough protest days in the five star luxury suites of Serena Hotel.

There is apparently a huge backlog of bills and receipts from the musical evenings, food, equipment, temporary shelter, containers that had to be arranged for the month long dharna. Who foots these bills? Where could this money have alternately gone? Does anybody even care?

Insincere revolutionaries

When thousands of Qadri’s diehard supporters were braving intense weather conditions and fighting against fatigue and hunger, no family member of the religious leader, including, obviously, himself, was there to share the misery of his protesters. They say when rich people fight wars with one another it’s the poor who die.

When the protesters started marching towards the Prime Minister House from D-Chowk, in accordance with the commands of their leaders, they faced rubber bullets and tear gas, while their leaders were safe in their containers and bulletproof vehicles. During torrential rains that followed, the devotees of Qadri, shivering with cold, were graced by one public address by their Pir, otherwise sleeping comfortably in his container, that the Holy Quran had advised Muslims to take refuge in patience during times of hardship.

The indifference towards the suffering masses in the sit-ins was also reflected in the official side of the story, which was terming these protesters ‘rebels’ and ‘terrorists’ without paying any attention to their genuine grievances. Our parliamentarians on September 5 met in the joint sitting and spoke not even a single word for the miseries of rain and flood affected people of the country. They chose instead to settle personal scores – Chaudhry Aitzaz Ahsan and Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan – and appease their injured egos. A single day’s proceedings of a joint session of the parliament costs about Rs10 million of the national income, a sum that could’ve been desperately used for the relief of the flood affected or the IDPs.

Political commentators said about the brawl of the two Chaudhrys, “These dharnas have resurfaced all the ugliness of politics. It’s obvious from these accusations on each other in the parliament that everyone is discredited in this game.”

Sincere conspiracy theories

“There is a script,” was the talk not only of the town but of the country. Every other politician and analyst claimed that the protest was part of a conspiracy to dislodge Nawaz Sharif. They said the premier was being penalized for committing the ‘crime’ of trying General (retired) Pervez Musharraf for treason, trying to open a trade dialogue with India by bypassing the military’s security concerns, trying to take the reins of the post-NATO retreat

Afghanistan-Pakistan relationship, and generally trying to enforce the supremacy of civilian rule over establishment organizations.

Afghanistan-Pakistan relationship, and generally trying to enforce the supremacy of civilian rule over establishment organizations.

News stories were published in some sections of the media that former DG ISI Ahmed Shuja Pasha had held secret meetings with Imran khan. A particular media group due to its friction with the country’s premier spy agency further propagated every theory of conspiracy.

During the joint sitting of the parliament summoned to seek support for the beleaguered Nawaz government, a number of lawmakers from the ANP, JUI-F, pointed fingers at ‘hidden hands’, further embroiling the military establishment in the propagation of the crisis.

Javed Hashmi’s revolt against the immovable Khan and later on his pressers in which he claimed that ‘some hidden hands’ had launched PTI and PAT came as validation for many of these analysts and media persons avowing the establishment conspiracy. But without any delay the ISPR issued a press release denying all claims that the army was complicit in any capacity.

As ever, the problem with narratives where the armed forces are concerned, is that much can be said but little proved. There are no safe avenues for investigation, nobody wants to put their heads on the chopping block. One can do little armed with just plausible theories against official denials, especially when the denials are backed with guns.

Still, the dust is yet to settle on this issue. This is perhaps the biggest lingering fear out of all the damage that has already been piled upon the civilian institutions, that sooner or later the hidden hand might reveal itself in the form of a direct intervention. The army chief has so far stayed his course, he has lived up to his promise of not interfering in political matters. But only time will tell how much substance these stories had.

Conclusion

The long marches may not have concluded yet, but their conclusion is largely irrelevant to the destiny of this state now. The damage has already been wreaked. The worst has come to pass. From the dithering politicians to the bankrolled cleric attacking state institutions with every second word he utters, from the belligerent and obstinate Imran Khan to a military happy to sit by and reap the power benefits of a civilian government under siege, from a ratings happy, gluttonous media to the hapless and hopelessly undisciplined and under-trained police forces; everybody involved, all of these actors, have succeeded in doing only one thing, destroying civilian institutions and the writ of the state.

For who will have faith in a law and legislature that has been so publicly disgraced both by a couple of rag tag mobs and the allegedly esteemed dignitaries supposed to be serving it?