By Muhammad Amir Rana –

The Urban Battles

The number of terrorist attacks in Pakistan considerably fell after the launch of military’s Zarb-e-Azb operation. After most parts of Miran Shah had been cleared of militants, security forces shifted focus on securing Mir Ali, Dattakhel, and Shawal Valley regions.There is no doubt that the operation in North Waziristan has helped in scaling down violence significantly; like the Swat and South Waziristan military offensives helped bring down the level of terrorist attacks by more than 30%. In the short to medium term the operation will help reduce violence in the Peshawar valley, FATA and, to some extent, in Karachi. These are the areas where terrorist violence has been concentrated over the past many years.

The military operation in itself is not a difficult task. Pakistan army has capabilities to reclaim and hold the area in a minimum time-frame. However, the political crisis in the country may affect and weaken political and military responses needed to counter terrorism and militancy in the country and distract from the administrative responses required in other parts of the country. This political crisis has hurt the coordination between the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and federal governments. At the same time, federal and provincial governments are not paying much attention to post-operation scenario.

They must not forget that the terrorists have an ability to disperse and protract their activities. In the post-operation scenario, the possibility of an enhanced or a reduced terrorist threat would largely depend on three factors, which requires serious attention of the government. First, it will depend on how tribal-based militants and their foreign allies behave and react. Secondly, it is quite possible that Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) allies and affiliates based across the country will not hesitate to launch attacks inside Pakistan. Among these groups, sectarian terrorist outfits are better organized and have the operational skills to trigger violence in the major urban centers of the country.

The third factor comprises a potential threat which cannot be measured unless it exposes itself. Militants in the making — radicalized individuals who are influenced by terrorist ideologies — can pose this threat. Though not ‘officially’ affiliated with any local or international terrorist organization, they are in search of such outlets. These kinds of potential militants could be large in number. Failure to find and join some ‘proper’ terrorist group can encourage them to plan and launch terrorist attacks by defining the targets themselves.

The militants can overcome their differences, restructure their cadres and reorganize their networks. Many religious scholars and madrassa teachers consider this segment of potential militants quite crucial as they are an important source of recruitment for militant organizations. They think that such militants are not only present in madrassas but in other educational institutions as well.

This threat is not new and can be understood by examining the emergence of the Punjabi Taliban during the Red Mosque crisis in Islamabad when militants of Kashmir-based organizations started leaving their groups to join the TTP and Al Qaeda. During that time, self-radicalized youths also formed small terrorist cells. These groups or individuals did not succeed in affiliating themselves with any terrorist group but were found involved in planning terrorist attacks by themselves. Such small groups were quite active in Islamabad, Rawalpindi and Lahore and carried out small scale, low-intensity attacks on cultural sites, girls’ schools and market places during 2008-2010.

In these critical times, making recruitments and establishing hideouts becomes easy for the militants. The state has been in denial and has chosen to overlook the fact that sectarianism is a big issue. It is thus underestimating the threat. The crisis in Iraq can provide insights into how terrorists create space for themselves through exploiting sectarian tensions.

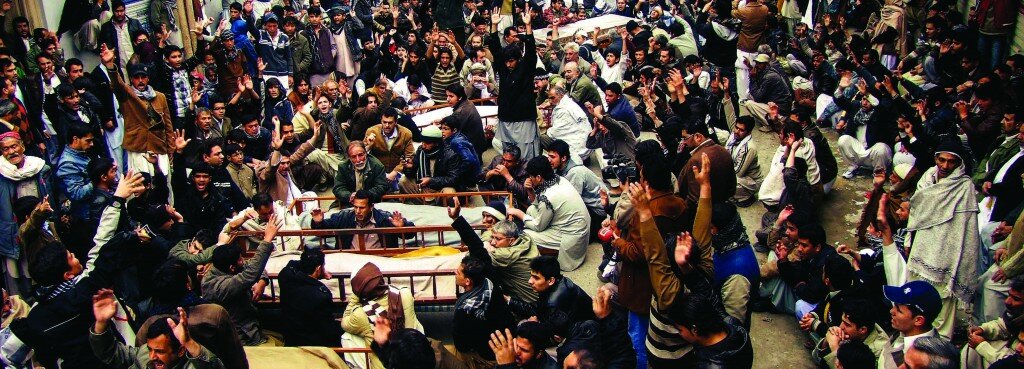

The spread of sectarian violence and tensions in Pakistan after the Rawalpindi incident on Ashura late last year was a clear expression of increasing sectarian divide in the country. At the same time a rise in sectarian violence that started in 2011 continued through 2012 towards mid of this year. According to Pak Institute for Peace Studies’ (PIPS) annual security report, the overall incidents of sectarian violence, including sectarian-related attacks and clashes, posted a slight increase in 2013 and 2014 as compared to 2012, the number of people killed and injured in these incidents significantly increased.

This is a major loophole in Pakistan’s security framework, which can lead to an escalation in violence. This weak area is the terrorists’ strategic strength. They can provoke sectarian tensions to get connected with their broader support base, which is maintaining a tactical silence because of the operation in North Waziristan. This support base includes sectarian madrassas and radical and even non-radical religious organizations. A single incident of sectarian violence can provide the militants an opportunity not only to connect with their sectarian and ideological support base, but also to exploit the situation and further expand the violence.

In this context, the state needs be vigilant and try harder to maintain sectarian harmony in the country. The current stand-off in Islamabad between the Barelvi, Shia allied Tahir-ul-Qadri and Ahmed Ludhianvi’s Sunni hatemongering ASWJ is a case in point; the political circus has let sectarianism come to the forefront once again, and it’s innocent Pakistanis who will pay the price.

The state, if unoccupied with other things, has many options available for this purpose, including engaging the clergy, positive initiatives through the media and enhancing security of religious processions and vulnerable religious places. It must deal with sectarianism as a strategic threat posed by Al Qaeda, the TTP and their affiliates. By leaving this loophole unaddressed, the state will never be able to successfully repel the militants.

The writer is a journalist based in Islamabad.