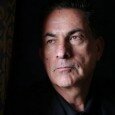

In conversation with Sheikh Waqas Akram

“He has a right to criticize, who has a heart to help.”

When Sheikh Waqas Akram speaks about the state’s shortcomings in combating sectarianism and militancy, he speaks as part of the resistance, as someone experienced and battle-hardened; he is a politician twice elected from a constituency which has become one of the breeding grounds for religious extremism in the country. Jhang.

After doing his masters in Information System Management from Central Queensland University, Australia, he could’ve spent a comfortable life abroad, well compensated, safe, away from the troubles of his hometown, but he opted to return and fight against the sectarian outfits which have turned the historical land of Heer into a place of hatred and intolerance.

He won the elections in 2004 against the sectarian Ahl-e-Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ) – the rebranded Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) – and became a Member National Assembly (MNA) from the PMLQ platform. He was given the portfolio of Parliamentary Secretary of Economic Affairs Division. He defeated the ASWJ again in the 2008 general elections, and went on to chair the National Assembly Standing Committees on Inter-Provincial Coordination and Petroleum and Natural Resources.

He became Minister of State for Overseas Pakistanis when the PMLQ joined the PPP-led coalition government in 2011. Afterwards he performed duties as Minister of State for Human Resource Development and later on was promoted as Federal Minister for Education. He remained senior vice-president of the ruling coalition from 2010-2012.

But It hasn’t all been a bed of roses. His family has been the target of death threats and assassination attempts, an uncle, a former member of the Punjab assembly, was killed in 1995 but it has never deterred Sheikh Waqas. He has never bowed his head to external pressures.

There has been a price to pay for it. He has survived three suicide attacks. He has also had to face a malicious vilification campaign and the wrath of the state functionaries who support extremist groups. His opponents hatched a conspiracy where they challenged his academic credentials to keep him out of parliament, in collusion with Javed Laghari, the former chairman of the HEC; a fallout from the days when Sheikh Waqas had forwarded cases of corruption against Laghari to the National Accountability Bureau (NAB). On appeal, the higher courts of the country dismissed the academic disqualification and cleared the Sheikh’s name.

While in office, he regularly attended IPU sessions in Geneva during his first tenure as an MNA. Sheikh Waqas managed to get Pakistan the chair of IPU anti-terrorism committee, first time in the history. He has delivered lectures on terrorism at Dallas University Texas. He also established a Parliamentary Caucus against Corruption in 2010 at home, to curb illicit political activities. He remained the Chairman Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FPCCI) think tank. He was interviewed by Zaynab Badavi for BBC talk show.

This month, Pique sits down in conversation with him to talk about his politics, his struggle against sectarian militancy, and his vision for the future of this country.

Let’s start off with that last bit. You’ve been in parliament, you’ve represented Pakistan on international forums. How do you see the future of this country in world affairs?

Pakistan is home to an extraordinary collection of people, who have existed in this land for thousands of years. We may define our identity as Pakistani for the last 67 years, but we also identify with ancient times, the Indus valley is home to one of the world’s oldest civilizations.

This region has always been a center of global affairs, as a vital trade route between the east and the west, rich with resources and fertile land, it has been of immense interest to kingdoms, merchants, invaders, historians, from Europe, Arabia, Persia, Central Asia and China.

It is important for the world to recognize that we have been here a long time, and we will remain here as a country that plays a role in the international arena, a role that few nations can even dream of.

We will define global security choices, we will take our place on the world’s economic chessboard and of course, we will be a decisive part of any international battles and paradigm shifts, between the individual and the state, between proliferation and disarmament, between a global order and anarchy. Whatever will be witnessed in Pakistan will become a part of contemporary history.

Therefore we have a role; the challenge for Pakistan has been the fruition of this strategic role, which has not completely dawned on our political elite. It has been understood by some in the establishment circles but not by our statesmen. We have only two historical examples of leaders who have displayed a realization of our manifest destiny, Ayub Khan and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

Though both achieved miracles for Pakistan’s global political prestige, what was achieved by Bhutto as a populist political leader was by far the bigger achievement and brought great dividends to this nation.

In the 70s we were the darlings of the so-called free world, the natural leaders of the Islamic world, and of course a beacon of light and hope for the economically forgotten nations, the dredges of colonialism. We were also the first country to become a nuclear state under a political leadership.

We have defended and established our sovereignty, our national agency, time and again, when we became independent from the yokes of an empire, when we consolidated that independence under the hostile shadow of India, when we stood up for the rights of the people of Kashmir, when we redefined the Cold War and when we blocked the NATO supply route for breaching our national trust. This agency comes from the inherent strengths of our geo-strategic location on the map of the world, and this agency will long continue in the same vein.

And what is your personal vision for the nation?

My vision for Pakistan is a country with a political leadership that understands the modern problems of a Westphalian nation-state, problems of neo-imperialism, non-state actors, pan-regional organizations, unchecked capitalism and trade liberalizations. Only the countries with a political leadership that understands these challenges to the dominion and authority of nations, and who have a clear concept of their role in a more integrated, more open world, will be able to establish the writ of a state and enable the latter to flourish.

Do you think we have a national identity, a unified narrative, or are we too disparate and scattered as a people?

Forging identities is a constant imperative for states, because they must define and redefine their existence in an ever changing world. The United States was once a union of white, landed slave owners. Now it calls itself a liberal, multicultural democracy.

In Pakistan we, as politicians, must take hold of our own narrative, and not let non-state elements give us labels. We define who we are and who we want to be. Politicians must eschew parochial mindsets and demonstrate the ability and will to lead a united people, define for them a new age in these times of flux.

I would like to think that I’m a leader who understands the realities and limitations of, and the opportunities which accompany, being a young nation while still having importance on a global scale, being territorially large, populous, being ethnically and culturally diverse; I have stood up against parochialism, sectarianism and other ills that erode the legitimacy of our state.

I see myself as someone coming from a grassroots level, a son of the soil, with the will, the energy, the patience to unite and lead the people for a common cause, and the common cause has always been Pakistan.

Okay, on to your politics. What’s been your biggest achievement as a minister?

I feel proud of the fact that I successfully lobbied for the first ever global initiative taken by the state of Pakistan. With the help of UNESCO we established a global girls’ child education fund, the Malala Fund, in December 2012, and I was one of the signatories for the project at the conference held in Paris.

We managed to bring as many as 138 education ministers from all over the world to this conference, in addition to the grand mufti from the al-Azhar University in Egypt, to present to the world the Islamic views on the importance of girls’ education.

The government of Pakistan itself donated $10 million dollars as seed money for the Malala Fund. The roots of this tree have already spread to multiple countries, and you will see it bloom in the coming years, educating thousands of girls around the world.

You have served as a Federal Minister of Education. What are the major problems with education in this country?

There is a great disconnect between the federal government and the provincial governments. When international organizations set a country-goal of education spending at 4% of the GDP, this target is given to the federal government to meet. But the federal government has no authority over provincial spending after the 18th amendment, and education is now a provincial matter.

Teacher training is also a big problem. There is no pride left in the teaching profession, it’s become an afterthought for career individuals. People get teaching jobs on basic degrees without any experience. Degrees that include MA Persian, MA Islamiat; not only are these not broad ranging, educationally empowering disciplines but these people end up teaching subjects that have nothing to do with their degrees. They fill any available space in educational institutes. Lack of vocational training leads to unemployment.

Worse still, is the politicization of the teaching profession. Because they are Presiding Officers during elections, their appointments, promotions and packages are directly related to their political affiliations. They can keep high posts as long as they fulfill these political functions, even if they can’t teach worth a dime.

Now a more charged topic. Do you believe in a dialogue with the Taliban?

No. Extremists have no reformist agenda within the mainstream ideologies and politics of Pakistan. People who don’t respect the law of the land, don’t obey the constitution, there is only one way to deal with them, using force. You can adopt a composite strategy, trying to de-radicalize the less extreme ones, the pliable ones. But the ones doing the most damage, the ones doing the recruiting, the brainwashing, the planning, they must be dealt with severely.

Do you believe in the distinction between good Taliban and bad Taliban?

The only good Taliban are dead Taliban.

Advocates of peace talks raise the following question: if the US can engage in dialogue with the Taliban, why can’t we?

The US was compelled to talk to the Taliban out of defeat, they were also thousands of miles from their homeland, hemorrhaging their military budget, and had already achieved one of their primary aims, to capture or kill Osama bin Laden.

This isn’t a manhunt or a matter of external war for us. This is happening within our borders. No peaceful outcome surfaced in our talks with Sufi Mohammed and Fazlullah. Ultimately our state was compelled to use force. Talks also failed with Baloch insurgents.

So how do you see Operation Zarb-e-Azb?

I don’t support talks with enemies of the state, but I don’t endorse half measures either. Security experts tell us that 40% of the militant leadership has fled into Afghanistan during this operation. What will happen when they return, or when NATO troops withdraw from our troubled neighbours in the west?

That’s an inherent problem with geographically limited operations. There is no real point to military force if Jihadi and sectarian outfits supporting and sheltering these terrorists aren’t thwarted in the rest of the country. The success and required results from Zarb-e-Azab can only be ensured with hundreds of small parallel operations in different cities of Pakistan.

You have personally been fighting against the biggest militant sectarian outfit in its stronghold, Jhang, what’s been your strategy?

My strategy is four pronged.

Firstly, to make people aware that there is a counter force, a parallel narrative to these extremists. History has shown us that social shifts are dialectic in nature. Wherever there is the potential takeover of extremism, there are also moderate and liberal forces ready to stand against it. But extremism is vocal, noxious, even in small amounts it can poison an entire community. That is why opposition to extremism must also be very visible, put itself out in the public space. Fighting extremism means keeping my doors open to people seeking refuge from it, at all times.

Secondly, to step in and provide vulnerable people the basic amenities and guarantees that the state is failing to do. These vulnerabilities are exploited by extremists. I try to ensure jobs for the unemployed and justice for the people without access to state machinery. I try to make sure that nobody harasses them, extorts money from them or evicts them from their lands.

Thirdly, being prepared for battles, turf wars, altercations, if needed. People must see that you are able to hold your own against brute force, if you are strong people will stand with you; if you are weak they will be wary of your promises of a different way, a better way. This means backing up my words with a force that has the capacity, the resources and the willpower to sustain a resistance.

Lastly, to open dialogue between religious leaders of different sects and encourage communal interaction, in an effort to keep the channels of communication open. Without communication there is no community, only mistrust and hatred. Not all their differences are negotiable, we are a nation deeply divided along sectarian and ethnic lines at the moment, but the idea isn’t to get them to abandon their fierce ideologies, but to start tolerating and respecting differences of opinion and practice.

Extremist leaders publish literature, hold public rallies and contest elections, are there stricter laws required or is it a matter of weak enforcement of existing legislature?

There are some vague laws but practically nothing to stop these people from engaging in political activities and contesting elections. When you invoke the laws that do exist, judges either interpret them to the miscreants’ benefit or dismiss your case altogether. They make asinine judgments to the effect that even if the organization is banned, the individual members and leaders who engage in politics aren’t. So they can occupy public space without using the banners of prohibited groups. The entire argument is senseless; the organizations get banned because of these individuals’ activities. Organizational bans achieve little anyway, their names get changed and the extremists continue spewing hatred under new banners.

This is a failure of the legislature, a failure of the judiciary and a failure of law enforcement. When I was in parliament I raised concerns over sectarian leaders flouting the laws of the state and continuing to engage in political activities, but I received no support, not from the other assembly members and not from the liberals and activists who profess to be committed to erasing the specter of sectarianism from Pakistan.

In these circumstances, much stronger legislation is needed to tackle this problem, legislation that takes biased ministers and judges out of the equation. If you want to curb sectarianism, you must cut these peoples’ political affiliations and their extra-legally protected right to publicly convene. We need brave officers to implement the laws.

Of the past military and civilian governments, which has made concerted efforts to curb militancy?

Of the past military and civilian governments, which has made concerted efforts to curb militancy?

In my opinion, since the creation of Pakistan, there has been no government with the inclination and willpower to battle sectarianism and extremism. They started caving in at the first anti-Ahmedi riots, and it’s been a long chain of openly or tacitly supporting these groups since then.

Musharraf perhaps made the biggest claims in this department, the Laal Masjid operation being his visible show of clamping down on extremism. But that was selective and self-interested clamping down.

I had the fortune, or misfortune rather, of getting a private audience with the General once, in the accompaniment of Brigadier Ijaz Shah, the former DG IB. I was trying to direct his attention to a sectarian leader of a banned organization who had been mobilizing political support and enjoying unrestricted movement from one district to another. I wanted the General to contain the man, if the laws were too weak to detain him outright. At which point Brigadier Ijaz Shah interjected and dismissed my appeals by telling the General that the person in question was their own man.

Musharraf’s operation and speeches were for foreign eyes and ears. It’s the same story in Pakistan’s history. Either the state has officially protected sectarian groups or individuals within the state have backed them in a personal capacity, with the full machinery of the state at their disposal.

Naseerullah Khan Babar once referred to the Afghan Taliban as ‘our boys’. Aftab Sherpao used to act as a liaison between the PPP and the SSP, and even got an SSP leader, Sheikh Hakim Ali, inducted as a minister. Ahmed Ludhianvi of the ASWJ boasted in 2010 that 25 PPP MNAs had been elected with his group’s blessing, the names included the likes of Shah Mehmood Qureshi, Jamshed Dasti and Faisal Karim Kundi. A recently sacked law minister in Punjab has been openly photographed at public rallies with convicted extremists.

And what about Jihadi organizations, are they an internal security threat for Pakistan as well?

While Pakistani society has endorsed and contributed enormously towards the Jihadi groups in Kashmir – and Afghanistan in the past – this social sanction is also problematic for the internal security dynamics of the country. Not because of any current internal threats from the Jihadis themselves, but because the militant outfits which have become anti-state and attacked Pakistani citizens have often used these Jihadi networks to train and recruit their men.

The example of Ilyas Kashmiri is a case in point. A veteran of both the eastern and northern Jihad, he eventually formed links with al-Qaeda and the Taliban, started anti-state activities and reportedly attempted the assassination of two army chiefs.

Masood Azhar is also a relevant example. He already had strong ties with the SSP before he went for training with Jihadi organizations up north under the influence and patronage of former Jamaat-e-Islami chief Qazi Hussain Ahmed. He then founded his own Jihadi group, the Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM), and made public statements that the SSP and JeM stood shoulder by shoulder in their mission to liberate Kashmir. The SSP and LeJ have used the JeM’s Jihadi camps for training their men.

Moreover, just because Jihadi organizations haven’t turned their official attention towards the Pakistani state so far, is no guarantee that they will never do so in the future. As their power and influence grows, so might their ambitions.

What about the Punjabi Taliban, is there such a separate entity?

Yes, they exist in as much as there are Punjabis who have gone to join and participate in anti-state activities with the TTP. There are also Sindhi Taliban, for instance, but the Punjabis outnumber them being such a larger proportion of the population.

The Punjabi members of the Taliban bring more technical expertise, generally coming from more urban, vocationally trained backgrounds. They are often the bomb makers, the strategic planners and the ones providing suicide and combat training.

Why do reasonably educated Punjabi men flock to the Taliban?

Because they are good employers, the Taliban pay well.

What has the Punjabi leadership, the PMLN done to counter these issues?

What can they do? The spokesperson for the party still refuses to admit that there are Punjabi Taliban. Nobody is prepared to face the reality that Punjabi sectarian groups are linked with anti-state terrorist outfits, which are in turn linked with international terrorist organizations.

But the PMLN is a political party, and like all political parties, they are so consumed with administrative concerns and consolidation of political power that they fail to see the writing on the wall until it’s too late.

When these sectarian groups were initially formed and gaining influence decades ago, these political parties dismissed them as rag tag outfits lead by two-bit clerics. And when they inevitably became monsters after years of international funding and supply of arms, the predictable reaction of the politicians was panic and fear.

But even more predictably, the next thought was how to channel this fearful development into political capital. All these two-bit clerics now had thousands of votes in every constituency, through the subscribers to their ideologies and through extorting loyalties with street clout and violence. So the idea quickly became to absorb them into the political system. To use them.

There is no political party in this country without local or regional alliances with sectarian outfits.

I gave a speech on the floor of the parliament some years ago, that the problem of sectarianism and militancy refuses to go away because our leaders are not brave. Of all their fears, the most crippling is the fear for the lives of their children and their families. Nawaz Sharif looks at what happened to Yousaf Raza Gillani and fears the same for his own son. This defines his political response to militancy. Look at Imran Khan who condemned the assassination of Kamili’s son standing on container but did not name or condemn the killers. His kids are still in London despite the formal announcement by PTI that kids will participate in long march.

This paternal fear is understandable, and wouldn’t be out of place for a normal citizen, but leaders have to make sacrifices. Either you can save yourself or you can save this country. If you cannot sacrifice your own children, then you cannot save the children of the millions of innocent people under threat from the same malaise. A leader who will be prepared to do that, can and will free this country of extremism.

You stand primarily against Sunni Deobandi/Wahabi organizations. Is there any bias at work here?

I oppose sectarian violence, not the ideology of any particular sect. In fact, any outfit, even outside the parameters of religion and sectarianism, which indulges in anti-state activities, hate speech, inciting murder and violence, should be dealt with, in my opinion, by the full severity of the law.

If Pakistan happens to be a hotbed for Sunni Deobandi anti-state actors, then that is where my fight lies. If the militant groups were of a different sectarian persuasion my reaction would be the same.

You mentioned these organizations’ funding. Where do these funds come from?

The two initial and long-standing major funders have been Saudi Arabia and Iran. They are the ones who started it all, the money, the ammunition, the pressure on elements within the state to overlook extremist activities.

When I was a minister I once visited the Saudi embassy in Pakistan for the crown prince’s condolence, to my great shock, a great number of these sectarian clerics were also in attendance, making no effort to hide their foreign patronage and the source of their funds.

As extremism has evolved however, some minor players have also started making their presence known. During Ghulam Hyder Wyne’s rule in Punjab, cheques to banned outfits were intercepted that had come through the Iraqi embassy. Then there were the Israel delivered Uzis found in militant camps.

These days, sectarian and militant leaders travel to Libya, Egypt, South Africa; Syria is the destination for Shia clerics; Dubai and the Emirates, the Gulf States, these are all financial wellsprings for these outfits. There are huge expatriate Pakistani labour populations in these countries, remittances and monetary transactions – informal loans, transfers – are often tied to sectarian and militant networks, under the prevailing ambit of the Wahabi/Salafi doctrines. Big businessmen and small traders are the national financiers of these outfits. Its a shame we have not been able to catch a single financier. Its easy but will is not there.

South Africa?

Yes, South Africa is a big source of financing for sectarian groups. Ten years ago, when the SSP was banned and its enforcers became wanted criminals overnight, they fled en masse to South Africa, where immigration authorities had loosened visa stipulations and liberalized citizenship laws, unaware what they would be getting into.

Since the SSP old guard still had ties with some politicians and policemen, they managed to have fake character certificates made, and were able to get their documentations ready.

What about al-Qaeda and ISIS and their similarities with TTP?

They all have the same core ideology, of imposing their own brand of Islam on this or that nation-state and forcefully removing any resistance. Beheadings, suicide blasts, the systematic oppression of women, defiling graves, tearing down mausoleums, these are all common modus operandi of the aforementioned organizations. While the slant of their ideologies might differ, their methods do not.

What about the role of the police in tackling terrorism?

The Pakistan police force is brave but kept untrained for decades by successive governments. There are two basic units of the Pakistan police, acting as the fulcrum upon which civilian law enforcement rests; the SHO and the DPO. These two vital positions are mostly hostage to political appointments, which means they bring to their jobs the political biases parties have towards one banned organization or another.

Even if by some miracle the appointment isn’t political, and on merit, the officer brings his own biases to the job. Police officers receive only law enforcement training, they don’t receive a well grounded administrative training or lessons on how to deal with sectarian issues.

Then there’s the handful of officers who shun both political appointments and personal prejudices to do the right thing. But they are completely abandoned by the state machinery they are supposed to be protecting. Chaudhry Aslam, the gung-ho officer who made battling militant organizations a personal mission, was repeatedly attacked until he was finally killed, and then the extremists killed his best sub-ordinate officer as well, while the state stood by idly and watched.

Why would a police officer risk his own neck when he knows the state will wash its hands of him and abandon his family and colleagues once he’s dead?

And the judiciary?

The problems of the judiciary are manifold. The police doesn’t provide enough forensic evidence for a prosecution. The existing laws are weak and often contradictory. There’s no formal protection for judges who give sentences and verdicts to sectarian leaders.

Then the judiciary itself is plagued by so many bureaucratic inefficiencies. The lower judiciary is in an appalling state. It takes the average man half a decade to get to the appellate courts. He has to drag his case through a Civil Judge, a Senior Civil Judge, a Sessions Judge, a High Court Judge, by the time he gets to the Supreme Court he has already sold his wife’s jewelry just to pay for the lawyers, and then the SC Judge takes five seconds to look at his plea and gives him a hearing six months down the line.

It’s pathetic. The authorities took enormous foreign aid for the improvement of the judiciary from the Asian Development Bank, the judges got new cars and expanded the walls of their houses, but little was done to alleviate the sheer burden of numbers on the legal system. We need more judges, faster trials, reformation of the lower courts, and then perhaps we’ll see some positive contribution from the judiciary in eliminating sectarian and militant elements.

You have been a frequent commentator in the media on the ongoing protests in the capital, what is your take on the long marches?

This entire fiasco has only had negative effects; it has weakened the state, undermined political authority, destroyed the institution of the civilian police and paved a way to the power avenues of the country for militant organizations.

I am of the personal opinion that the script behind this entire drama wasn’t just penned locally, it was an international script; written probably by the MI6, facilitated greatly by some of our retired establishment dignitaries and out of season politicians. MI6 are expert script writers, the CIA used their ‘Mossadeq ouster from Iran’ screenplay for over forty years.

You contested the 2002 elections against Tahir-ul-Qadri, what do you make of him as a leader and as a person?

When Tahir-ul-Qadri stood against me in the election campaign, his political posters had just one thing blaring in bright red ink, ‘The Sunni Prime Minister’. The slogans chanted at his rallies were also to the same effect, ‘Sunni Prime Minister’. He wanted, and still wants, to be the PM of this country. Like any other Mullah he wants control.

Unfortunately for him, there is no electoral scope for a cleric, no matter how many alliances with Christian community leaders, Barelvi organisations and minority Shia groups – and the Majlis-e-Wahdat-e-Muslimeen (MWM) is a minority within Shia Islam – he makes. There is just not enough political mobilization of Barelvis to help him achieve his goals.

The revolution is a smoke screen. He realized after 2002 that he could never come through the system, through the electoral process. He could only be a spoiler, never the winner. So this revolution is his only chance of achieving a lifetime ambition, and both his open and clandestine supporters have given him sureties to that effect. That should the incumbent government topple, he will be close to the top of the power pyramid.

Still I have to hand it to the man. He’s nothing if not shrewd. He comes from a very humble background, a very poor family in Jhang. He used to ride a bicycle in 1976 and had a wooden platform at the Jhang Kacheri from where he practiced law. Now he’s made it to the international arena, there are billions of rupees being spent on him, and the bicycle has been replaced by land cruisers. He leads his revolution in a bullet proof, custom designed, luxury container, you can’t deny his ambition for self-betterment.

After you quit your last party you had a choice of joining either the PMLN or the PTI, why did you choose the former and not the latter?

When I was in college I was already involved in politics. I was the district president of a student organization, and when Imran Khan was newly married to Jemima, I got to spend 2-3 months up close and personal with the newly turned politician.

During that time, I listened to a lot that he had to say about politics and Pakistan in general. I realized that he was a man who loved to talk, a man who loved the sound of his own voice, but there was very little substance backing up the talk.

When I started Pique, my team interviewed Imran Khan once. I got the chance to listen to him again after many years. He was still the same, a lot of talk, but little substance.

He talked about change, but was vague on how to go about implementing it. To put it simply, I was not impressed. I’m still not, but politics isn’t set in stone, and leaders learn and change. Someday, perhaps.

What about the question of saving the system, the question of democracy?

Democracy isn’t just going through a ballot and forming a parliament. Democracy is also about an attitude. There can be no democracy when the political leaders espouse dictatorial attitudes in governance. No political party listens to its workers, or even some of the elected members of its party, once in office.

What about electoral reforms?

Elections are a dynamic process, there is no method set in stone to ensure free and fair elections. Reforms are always necessary due to both administrative weaknesses and evolving technology. The Americans still have electoral reforms after all these years, they do them with patience and introspection however, not by tearing down state institutions.

For my money, Returning Officers should indeed be from the judiciary. In the Gujrat by-election, when they called in a political RO, a grade 19 EDO from Sukkur, the result was a disaster. Judges are, in general, harder to bribe and coerce. But, this continuation of the RO policy should be on the strict condition that the judges are not ROs in their own districts.

The issue of POs coming from the teaching profession has caused immense problems in state education, but can also be resolved by shuffling their districts. Teachers should be allotted districts at random at an appointed time before the elections, so that the previous five years aren’t spent with the district MNAs wrestling for educational appointments and providing patronage to teachers who aren’t interested in their day jobs.

The Election Tribunals should have serving, not retired, judges. High Court judges can be granted a 3 month leave for the express purpose of hearing election disputes. Retired judges are easier to intimidate and coerce.

How do you feel about the violations of human and women rights in the country?

Any form of human rights violation is condemnable but the double standards of social and political activists tend to annoy me. If a Christian girl is put behind bars over a blasphemy case, all the NGOs in the country come to her aid. But I know of a case in which a Muslim girl is languishing in jail over false charges of blasphemy, when I asked notable human rights activists to raise their voice on her behalf they offered only platitudes in reply.

There should be consistency of activism, based on individual cases, not organizational agendas.

What is your take on ‘Aman Ki Asha’ and Pakistan’s relations with India?

Dozens of Indian hearing-posts along the border of Afghanistan and India’s dubious activities in Balochistan undermine efforts like ‘Aman Ki Asha’. It was even backed by Pakistan’s establishment in the beginning, it was a genuine attempt on our part, but it lost its luster due to India’s continued machinations against us.

India must accept Pakistan’s existence as a player in the regional politics of South Asia. Neighbouring countries should have friendly relations with one another, but on an equal footing, from a position of balance. The issue of Kashmir should be decided in accordance with the UN resolutions first, that would be the beginning of a real diplomatic relationship.

How do you see Pak-China relations?

China is dumping its low quality, substandard manufacturing in Pakistan. They call Pakistan a graveyard for Chinese MoUs but Pakistan has also become a junkyard for China’s worst trade items. China’s banks offer exorbitant loans on sovereign guarantees and China’s investments are laced with asset losses for Pakistan.

They are essentially sucking us dry, taking advantage of our poverty and desperation. They don’t have qualms like the EU and the US, no structural adjustment programs, no human rights requirements, no aid dependent upon social reforms, so our statesmen look east for quick fixes and big, visible projects.

But make no mistake, this is not a friendship, it’s an exploitative relationship. India’s trade volume with China is much bigger, and the quality of that merchandise much better, the only loyalty the Chinese seem to have is to their own businesses.

Pakistan has already suffered huge monetary losses due to the procurement of substandard locomotives from China during the previous two federal regimes, when Javed Ashraf Qazi wasted money on 75 locomotives and Ghulam Ahmed Bilour on 69, while they were holding the railway portfolios.

Most of the Chinese companies are state owned. They are big on commissions and kickbacks. The government of Pakistan should officially convey to China the names of the companies that are coming here and making a mess, otherwise it will result in an eventual deterioration of Pak-China relations.

Why do Pakistanis consider America to be enemy number one, even ahead of India?

People from this region have historically identified with the concept of a global Muslim community, one which transcends regional boundaries. Sometimes this concept has been self-defeating, as in the case of the ill-fated Khilafat movement before independence, but it is what it is. As long as the US is involved in Muslim affairs all over the world, people will always nurse a lot of hostility towards them.

The US shouldn’t expect this to change anytime soon. In any case relationships between states are based on mutual interest, and not necessarily kind words. It is still in their own interest to continue this somewhat paradoxical relationship with Pakistan, cordial on a diplomatic level, but acerbic on the streets.

What are the skills required to be successful in the realm of politics?

If you read Sun Tzu’s ‘The Art of War’, you will learn everything possibly required to become a statesman and a leader.

Sheikh Waqqas Akram tweets @SheikhWaqqas