By Rabia Ahmed –

Terrorism, the single most distressing worldwide problem today makes this novel by Nicholas Shakespeare even more interesting

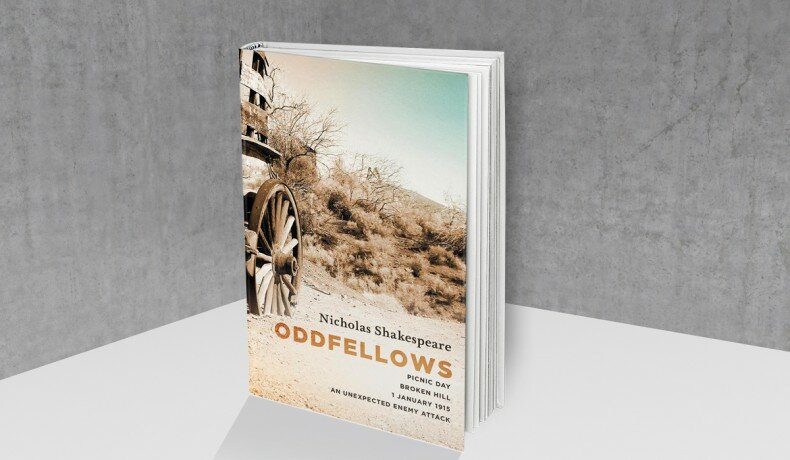

Terrorism, the single most distressing worldwide problem today makes this novel by Nicholas Shakespeare even more interesting. The book, subtitled: ‘Picnic Day, Broken Hill, 1 January 1915. An Unexpected Enemy Attack,’ refers to a real attack on Australian citizens that took place at Broken Hill in New South Wales, Australia, during World War I. That attack was an Australian Pearl Harbour, the first ever (but not the last) ‘enemy attack’ on Australian soil.

In an attempt to open up the vast sandy desert in the middle of the continent, the British in Australia brought in camels along with their camel drivers from India, Afghanistan and Turkey. These men led strange lives in their new country (their lives are beautifully documented in ‘Tin Mosques and Ghantowns: A History of Afghan Camel drivers in Australia,’ by Christine Stevens, also referred to by Nicholas Shakespeare). Muslim or Hindu, they lived in their own segregated settlements, discriminated against for reasons of race and religion.

In November 1914 the Ottoman Empire entered the First World War on the side of Germany, Turkey, Bulgaria, Austria, Turkey and Hungary. The sympathies of the camel drivers in Australia lay with the Ottoman Empire which was in the war against Australia.

It is against this backdrop that the Broken Hill incident took place and this book is written. Shakespeare has taken the essential components of the incident and surrounding them with an entirely credible but fictitious story: there really was a ‘Molla’ Abdullah, and there really was a Gul, local imam and halal butcher, and ice cream vendor respectively. These were the men who fired upon a group of picnickers, killing four of them at Broken Hill on New Year’s day.

Some aspects of the story are a warning, particularly for us in Pakistan, such as the fact that Abdullah and Gul suffered grave social injustice within the community. They were forced, because of various humiliations to identify with a past, and turn to an ignorant version of religion that they had in effect left behind but could not forget. In a gesture symbolic of his reversion, Abdullah put on a turban on the day of the attack, an item of dress he had abandoned ‘since the day some larrikins threw stones at me.’ Both men tailored Turkish uniforms for themselves, and stitched themselves a flag with a crescent and moon to resemble the Ottoman flag to wear on the day.

Some aspects of the story are a warning, particularly for us in Pakistan, such as the fact that Abdullah and Gul suffered grave social injustice within the community. They were forced, because of various humiliations to identify with a past, and turn to an ignorant version of religion that they had in effect left behind but could not forget. In a gesture symbolic of his reversion, Abdullah put on a turban on the day of the attack, an item of dress he had abandoned ‘since the day some larrikins threw stones at me.’ Both men tailored Turkish uniforms for themselves, and stitched themselves a flag with a crescent and moon to resemble the Ottoman flag to wear on the day.

In his confession Gul wrote, ‘I must kill your people and give my life for my faith by order of the Sultan because your people are fighting his country.’ This referred to an appeal made by the Sultan of the Ottomans a few weeks earlier for all Muslims young or old to fight against the Entente Powers, ‘the mortal enemies of Islam’.

Interestingly, in the aftermath of the incident there were few repercussions against the Muslim community, when compared to those following the hostage incident in Sydney in December 2014 in which three hostages and the hostage taker were killed. The Sydney incident though was also known for the hashtag #illridewithyou accompanied by sympathy for the greater Muslim community. Instead, in 1915, because the public was so focused on the Germans, it was believed that the men were acting under German orders, therefore the German club, was torched that night. Also, far away in the Saxon town of Freiberg, a newspaper read: ‘We are pleased to report the success of our arms at Broken Hill in Australia. A party of troops fired on Australian troops being transported to the front by rail. The enemy lost 40 killed and 70 injured. The total loss of Turks were two dead.’ That was Abdullah and Gul.

This is how it always is, the reasons, the repercussions, public perception and reaction, the way the matter is dealt with by the media, followed by its consequences. It is a well rounded picture.

Shakespeare has delved sensitively into minds on either side. In the end the naked bodies of a victim and one of the shooters, Gul, lies side by side in the hospital, their knees and hands almost touching…both humans, both exactly what life made of them.

Born in England, Shakespeare grew up in the Far East and South America. He has worked for the BBC, the Times, the Daily Telegraph and the Sunday Telegraph, written several books fiction and biography, and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He has received several awards, and in 2012 was confused with William Shakespeare by the then French presidential candidate François Hollande when he said: “Let me quote Shakespeare, ‘they failed because they did not start with a dream'”

This book is published by Vintage, 2015.

The writer is a freelance journalist and art critic based in Lahore