By A Rahim Khan –

Pique’s exclusive interview with Senior Scientific Advisor at the ESA’s Directorate of Science and Robotic Exploration, Mark McCaughrean who speaks at length about the Rosetta mission

Famously, science fiction doyen, Arthur C. Clarke, ventured, as a young air force officer who occasionally dabbled in fiction, the idea of communication satellites. Proposing the launch of ‘artificial satellites’ into Earth’s orbit, these machines would serve as ‘repeater stations’ or relays for global communications, transmitting everything from televisions broadcasts to phone calls, creating the ‘small world’ we have today.

The year was 1945, and while fame as a writer and indeed the satellites themselves were still decades off, this flight of fancy was on the cusp of reality, the now welcome trope of science fiction becoming science fact.

Of course, while the original proposal was not purely fictive; it was offered in earnest to a tech magazine, it nonetheless represented a moment, in a continuing tradition, of the envisioned tomorrow becoming the actual today.

Space stations and trips to Mars, leaving the Solar System and discovering other Earths, all would have seemed fantastical a decade or two ago, but now they are facts unto themselves, achievements, truly human.

Of course, each of these ideas, in conception would have appeared inane and wholly impossible but time proves to be the best reckoner and if 30 years ago, the idea to land a probe on a moving comet, those cosmic wanderers, would have sounded certifiable, then today we stand most humbled.

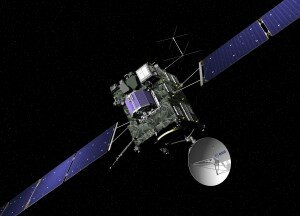

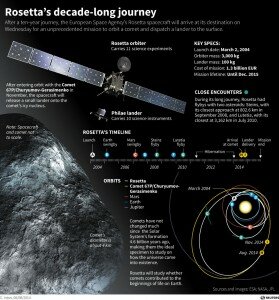

On November 12, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) spacecraft Rosetta, successfully deployed the lander Philae to the surface of the comet 67P, itself hurtling towards the sun. On paper, the ambition and scale of the mission may be done a disservice for the feat in itself is incredible. Out in the vastness of space, Rosetta, after a 10 year journey, homed in on the ball of rock and ice known as 67P, millions of kilometers from Earth. It then got in close enough to deliver its payload, marking the first time in human history something manmade had touched down on a comet, fiction crossing over into fact.

The culmination of decades’ of work, the Rosetta mission sought to study a comet, witnesses and possibly even particpants to the creation of our planet. Whether it was this aspect of the mission or its audacity, Rosetta garnered public attention like no other, creating the kind of fanfare that is usually reserved for pop culture.

With Philae presently ensconced on 67P and Rosetta trailing behind, the orbiter will act as the comet’s consort as it makes its way to the sun, giving us front row seats to a very singular experience.

In an exclusive interview with Pique, Senior Scientific Advisor at the ESA’s Directorate of Science and Robotic Exploration, Mark McCaughrean speaks at length about the mission so far and its significance beyond.

Pique: Congratulations on the mission so far…

Mark McCaughrean: Thank you very much; I think we all feel very privileged and very proud to be part of something quite so amazing. We knew technically how great it was, we knew technically how difficult it was but to be quite frank we were not really prepared for the colossal amount of interest we had from around the world, it’s been great to actually share that, it’s been quite something.

The last couple of weeks must have been exciting yet very tense, can you describe the atmosphere at mission control?

MM: People have been working a long time since we arrived in August at the comet and we did something completely unusual within the space of three months; we actually had to go from arriving at a totally unknown object to actually then putting a lander on its surface. It’s a completely strange object because comets are not only as we’ve seen, very, very oddly shaped which means the gravity keeps on changing all the time; the gravity’s weak but we’re still subject to it. And also it’s active, which means there’s material flowing away from it. So in the weeks leading up to the landing, people were working really very hard. There were tensions there because the comet was much more complex than we expected so there were great worries about whether we would find a place that was clear enough to land, so I think tensions were extremely high.

In the immediate days leading up, everyone was extremely focused on ensuring all the technical aspects of the lander were prepared, that we were on the right trajectory and I have to say, and this is a point that we can’t say too many times, the guys and girls that drove us onto the surface and dropped the lander off, they did an absolutely astonishing job, I mean they will be heroes for years to come for getting us a 100m off the landing point.

Of course as late as the night before, 02:30 in the morning, just a few hours before the go/no go, we were very close to postponing the whole thing. There were issues that were arising, software signals that were coming back from the lander that we didn’t understand, a number of, let’s call them failures, things that just shouldn’t have fired. That night, we had got to the point; I would call it minutes away from actually not cancelling, but scrubbing the landing. And that scrubbing would have involved waiting maybe 19 days until we came around in orbit again, with Rosetta, to get back in the right trajectory – this wasn’t going to be a 2 hour delay or something, it would be a matter of weeks.

So at that point, fortunately again, the teams managed to work through all of the software issues, they were downloading the software through the orbiter from the lander, trying to debug it. And fortunately people began to piece the picture together, to the point where we said that we do have one failure, we don’t seem to be able to activate the small retro thruster we have on the top of the lander to hold it down but more broadly the other issues seem to be things that could be overwritten, software things that had failed for reasons we understood. So fortunately we went ahead but it meant that next morning things were extremely tense when it came to pushing the lander off.

On that morning, I think because it’s been 10 years in flight, 20 years in the making, maybe 30 years by some estimations, I think there were some people who were anxious to just get the lander off, saying let’s just let it go.

So there was a great deal of relief when Philae went on its way and as I said at the time, at that point we were in the hands of Isaac Newton more than we were in the hands of software and everything else. Of course, this then led to a very, very tense period during the day as we waited two hours to get signals back from the lander because the orbiter had to go off on another trajectory and we couldn’t turn the antenna back for a couple of hours so there was a relief there. It was a series of, if you like, increasing incredulity; there was so many ways it could’ve gone wrong so every time something went right, it began to feel that we were getting really luck here. But what was coming? What was still around the corner?

We were not driving down to the surface, we were falling. We had some idea, at any given moment, how far away the lander was from the orbiter but not where it was and even though the lander had cameras, there weren’t being used for guidance to say let’s land over here, let’s land over there. I mean, effectively, we were falling to wherever we were falling. And there was always this concern that the surface of the comet was going to be rough and we knew it was and that we would have trouble. But when we actually had that first touchdown moment, the sense of exhilaration, which I’m sure everyone saw and shared in, was absolutely immense – we had come down on the surface of a comet, it was spectacular.

As you said, this mission has been 30-years in the making. Of course, the very idea of landing on a comet sounds very outlandish; at what point did this almost wild idea become a serious scientific mission?

MM: Well, the 30-years timescale even goes back before the ESA’s Giotto probe which flew past comet Haley in 1986. Of course with comets you know how long they take to go round the Solar System and with Haley, effectively being the most famous of the comets, people knew it was coming back after 76 years. People thought we could do that in 1986, that we could build spacecraft to fly past a comet at very high speed; I mean the high speed isn’t because we’ve put it on a fast rocket, the best we could do was get on the same orbit as the comet and intercept. People were already thinking before we had that encounter that the best thing we really want to do is get up close, study a comet, watch it evolve and at that time, grab some samples and bring it back.

The original mission was actually going to be a joint ESA-American mission. Giotto was successful; there was a lot of momentum behind that kind of science and building a mission of that kind. The Americans had budget troubles at that point and pulled out, so the mission was descoped down to something which instead of bringing samples back down to Earth, actually put small laboratories on board (a lander), science in situ. So I think by the end of the 80s there was a lot of momentum there, people had worked out pretty much how to do it and our process here, people propose missions from the scientific community, we evaluate them technically, there’s a competition, you have winners, you have losers, and so what became Rosetta in the end was picked and more or less decided by 1994. Then there was a 9-year build process, we got done by around 2003 but not ready in the end cause we couldn’t launch in 2003 because of a rocket failure which then postponed all rocket launches for a year.

So in a sense, the technology we’re flying was pretty much identified, pretty much put in place by 1993-94, of course by the time we finished building it in 2003, technology had changed and so for example detectors on board reflect technology from about 1998 or 2000. So we’re still a long way behind, with 15-year-old technology on board but of course it was very, very state of the art at the time. As I said to somebody before, people say well you’ve only got a 4 megapixel camera on board, well I’ve got one of those in my smartphone – that’s true but at the moment, in space, I have a 1 gigapixel camera.

With so many missions presently studying the Solar System and beyond, why study a comet?

MM: Comets are, effectively a treasure chest of material from the birth of the Solar System. Our planet Earth, was made of course at that point, 4.6 billion years ago but has been processed, it’s changed. We have plate tectonics, we have evolution of the geology, so it’s very, very difficult on the planet to get to the original material which the Solar System was made out of and try to understand the history of the Solar System from that. The comets have that because left over material from 4.6 billion years ago was put in deep freeze and if you do what we’ve just done, you can actually go and get into that deep freeze and find that left over, take away dinner, and it’s still there. You probably may not want to eat it, but you can at least examine it.

There’s a kind of history story encoded into comets but the critical thing beyond that is they contain two key components to us personally and that is the model we have and still hold from our investigations so far of 67P is that comets are roughly 50% water, in the form of ice, there’s other stuff, like carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, lots of trace elements, but a lot of ice. One of the big questions about the formation of the Earth or the early history of the Earth is where did all the water come from? There may be many people who say, it was here but probably not, cause the Earth was very, very hot when it was young. There are models which say that the water could have been locked up in the rocks and it came to the surface later but the competing theory is that the water came later and came from comets, maybe asteroids. We know that these collisions happen even today – the event at Cheylabinsk (Russia) and the meteor crater in Arizona (USA). We’ve even been hit by comets; we saw Jupiter hit by a comet in 1994, the famous Shoemaker-Levy 9. So we know that these collisions happen today but in the early Solar System there were many, many more of these objects around and the big planets at the time were like vacuum cleaners that hovered up these objects and many, many asteroids and comets will have hit the Earth in the early phases and could well have delivered our water.

So if we go back and look at comets which are still sitting out there, maybe we could try and see what water it is because not all water is created equal, they can have different isotopic ratios but also look at what else is in there – if it was water that was delivered, what other materials were delivered at the same time? One of the key components is carbon-based molecules, complex molecules. We know that you see these things in space, if you go look in regions where new stars are being born, you can see quite complex carbon chemistry but again how did that get to the surface of the planet?

Well, if that material was locked into a matrix of ice and dust in comets then maybe that material was brought to the surface. And a very interesting, recent result is even though comets might contain relatively limited amounts of complex stuff, amino acids and the like, if you take the simple molecules, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, methane, ammonia, if you then crash that object at high speeds into a rocky body, the collision energy involved will actually shatter those molecules and give enough energy to turn them into much more complicated chemical elements. If you do experiments where you fire a bullet at high speeds into comet material, you get, with just very simple material even, much more complex material out of it. So that’s the sort of fascinating idea that the collision of the comets themselves created the building blocks of life. That’s quite a remarkable thought.

There’s something quite ambitious, even forward thinking about the Rosetta mission, do you think that this is lacking in space exploration today?

MM: It’s a very good question. We made a lot of it…it sounds manipulative but we knew how risky this was, it’s never been done before. We arrived in August and we suddenly had to learn how to operate in a way that nobody had ever done and again hats off to the guys that figured it out so quickly. But it’s certainly the case that you try to buy down all the risks, you try to put in place all the mitigations but if you do it to a point where you say let’s not try something difficult, then you’re missing the point cause there is a big picture here. And the big picture is that we do space because it’s interesting, we do space because we think there’s scientific and cultural value in exploring the universe around us but to be quite frank the bigger point is that we do these things to inspire, we do this because people want to be and should be lifted out of what is a pretty difficult life we all live, I mean particularly in the world today, there’s many problems we have to face on the planet Earth, and that’s not to say that we go to space to solve these problems – people constantly make this comment that shouldn’t you spend the money on Earth, well it is all spent on Earth, we don’t send money into space, people get jobs out of space.

But the inspirational value of convincing people and showing people that by being ambitious, by being willing to take risks but working really hard to mitigate those risks, to study hard, to try and be as rational as possible about the task you’re taking on, for me personally, that has colossal value on the planet earth that people now, kids of 5, 10, 15, even adults will look at what we did last week and say you know those guys and girls pulled that off by thinking really hard about it and it’s not just the same as sitting down in front of the television and saying ‘entertain me’. And we need that cause for me, the only way out of the problems we have on this Earth are partly by technology. But also beyond that, rational thinking, discussion, debate, disagreement. How do we actually process problems? We need to learn that and in a very small way, missions like this can gather people’s inspiration. As long as they don’t just see it as an entertainment show in which you turn the pictures on and you think they’re pretty and you turn them off again, people have to understand the process that went into doing what we did, I think that has value.

Compared to other recent missions, Rosetta has a considerable social media presence, was that always the intention?

MM: Yeah, it was absolutely the plan from the beginning. I mean, with all of these things you kind of make it up as you go along. There’s lots of social media, there’ve been lots of missions before, like Nasa’s Curiosity mission, which had the world watching for those 7 minutes of terra. But we knew we didn’t have those 7 minutes of terra, firstly, we had a mission that didn’t rely on the landing at the end; the Rosetta probe itself, the orbiter is very successful and it will be there for another year so we have a slightly different mission and it’s one of the reasons we made Ambition, a science fiction film. People have wondered why did you do that? Why didn’t you do a technical film? Well, a technical film would’ve been very boring. We wanted to talk about the inspirational value, what it means to take on these problems. So we thought very hard about how to do this.

You know there was a point at which, in a great way, this thing actually took off. When you have Google come to you and say we want to do a Google Doodle on the day, the UK Royal Mail say we want to stamp every stamp going out of the country with ‘Congratulations to Rosetta and Philae’ and guys like you are interested in talking to us and spreading the message across the world, I mean you plan for that, you hope for it but you can’t guarantee it.

I think Rosetta had a number of things going for it. The history: it’s been 30 years, it’s been flying around the Solar System for 10 years, people buy into that kind of long term planning. It’s a very visceral thing, you go to an object, you take a picture of an object, and you land on an object, that’s very different to many of our other science missions which are a bit more esoteric. People understood that it was risky, that it was going to be difficult. And the comet turning out to be so spectacularly complicated probably raised interest too.

We did take one risk, one big gamble which I think paid off very well on the media side and that was when we had the ‘wake up’ in January; the probe had been in hibernation for two and a half years. Now I’m a scientist myself, I’m the senior scientific advisor here so I’m very heavily involved in communications, so a lot of people at the time said no media, nothing. Let’s just wake it up and put out a press release the next day because we don’t really want to have the media if Rosetta doesn’t turn on.

Our attitude was really strong though, we were like look, you’re going to face a post mortem if it doesn’t turn on but think of the positive value you can gain if you can engage people in a ‘waking up’ campaign. So we made cartoons, we had competitions. And what that did for us is firstly engage the public straight away, cause you know it’s relatable – being asleep, waking up in the morning, these are human things. And on the other hand it helped wake up many in the media so we had people coming to that who said ‘Ah, I can get in early here’ and make a documentary about this. We’ve had documentaries made by National Geographic, Discovery, European channels. It wasn’t just a story that could be told on the landing day but a story with a longer baseline, allowing for a kind of buildup of the buzz.

We were happy, so happy to see what happened last week but my goodness we couldn’t have planned for something like that, it was insane. There was a point when we were actually looking at each other and saying what have we done here?

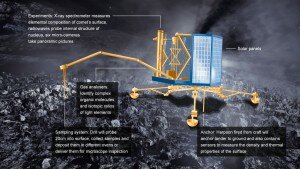

We know that since touchdown on 67P, Philae has gathered quite a bit of data and while premature, are there any initial impressions of what it has discovered?

MM: Well, you know that’s another one of the public expectations. It’s interesting because of the way we’ve kind of portrayed this as a real-time adventure, you get there, you do things, you land, there’s kind of an expectation that the science comes immediately after. Of course, normally in science it could take months or years but we’re putting out results which are very preliminary about this solid ice that we’ve landed. We’re going to get the first results of what the interior of the comet, well, not what it looks like but whether it’s hollow, its porosity etc. We’ve been sniffing the material around the comet; we’ve been detecting lots of organic molecules.

So I don’t think there’s an integrated picture yet but snippets of results. A lot which comes out, which will be in a fairly preliminary form will be at a big conference in the US in a few weeks time, the American Geophysical Union.

I think there’s no synthetic view, there are as many surprises in terms of the structure, the way the comet looks, the evolution of the comet, how did it get to be in this shape as there are confirmations of the general theory of comets. There’s lots to learn, nobody’s ever been this close and has this much information. It’s certainly early, but the indications are that we have the richest data set imaginable already.

But, the critical thing is we’ve actually arrived at one of the most boring times in the life of the comet, deliberately to get on the surface before the comet comes to life. So the critical thing that everyone has to remember is that next August , it’s going to be a fantastic time as the comet comes to life and we’re going to be sitting there, watching this thing change every day as it passes near the sun, nowhere as near as the Earth is. That will dramatically change what we see every day. The answers don’t come from Philae alone; they come from Philae and Rosetta together.

What do you think will be the significance of this mission in coming years? What do you think its legacy will be and what do you think it’ll pave the way for?

MM: You know that’s a great question, and I think it’s a little bit early. We all had hopes that this will open new doors and as I said before, not only in public engagement, public interests, public excitement, but I mean there’s a very Eurocentric aspect in that the people will now see the ESA as a direct peer to NASA. You know frankly, living in Europe, that’s not true for many Europeans before last week and we’ve changed that forever. And that’s very important; Europeans need to have a feeling that we are capable of taking on big, ambitious things. The Americans are very good at selling that message, which is a big part of their culture and we now know that other countries around the world, China, India, Brazil, Japan are also getting active. There’s also a degree of national pride, in our case continental pride.

Of course, getting to the kids, getting to the people, that’s important. But say with politicians, when you ask them for money as an organization, they’re constantly being asked for money so they tend not to give more money than they can get away with. The better way to get money from them is if they’re pushed from behind, if the public say we think this is great stuff, not just to give us money to go and do things in space but again the science is important, the technology is important and that it can be inspirational, then for me that would be the ultimate legacy of this and it raises awareness that you can do great things by thinking and working and collaborating. I mean this is a big international collaboration, and for Europe, a continent which was 60 years ago at the tail end of war, we’ve come together to do this, it’s quite a remarkable achievement.

In the near term, we have what is called a Council of Ministers, which is funding round in a few weeks time and hopefully that will yield great advantage. That people will see that they should fund these things. But beyond that it’s a much bigger picture for me. I have young kids and I really want them to live in a world that to some extent we’ve screwed up over a couple of generations and it’s not that going into space is going to fix it so much as creating an inspirational aspect about how humans can come together to do amazing things.

The writer is an Islamabad-based journalist