In a world where lives are conducted through text messages and e-mails, why is our language still stuck on black boards and slates?

If literacy is the ability of persons fifteen years of age and over to read and write then here are some sobering facts for Pakistan: In 2009 according to an estimate just 54.9% percent of the population of Pakistan was literate; broken down by gender only 68.6 % of Pakistani men and 40.3% of women could read and write in 2009. By July 2014 Pakistan’s total estimated population is likely to be 196,174,380. If those same percentages for literacy hold true (and little appears to have changed) there will probably be 88,278,471 persons unable to read or write in this country by the middle of this year.

Of course, Pakistan is host to a plethora of other problems too, terrorism, corruption, poverty, the oppression of women, the population explosion, poor public health and the devastating power shortage; but illiteracy has an impact on each and every one of them. A nation as illiterate as Pakistan is prone to social unrest; its illiterate women are more likely to be oppressed by illiterate men, themselves oppressed by poverty; its population is likely to be large and unhealthy, and one that is unable to provide for oneself, fewer employment opportunities existing for those who can’t read or write; social development is slower with an illiterate population and more resources have to be spent tending to their needs, resources that could otherwise be spent on power projects.

Most people working in the education and development sectors acknowledge the above, so what’s stopping us from improving the situation? To be sure some of the problems are logistical, there seems to be a dearth of infrastructure and teaching staff, some are political, education has never been a priority in our corridors of power, and some are financial, making people literate takes money, sizable investments.

But there is another kind of problem too: the problem of language. The above mentioned statistics on literacy are based on the criteria that the person is able to read a newspaper or write a letter in any language. Pakistan has two official languages in which state business can be conducted and legal matters settled; Urdu and English. It also has many provincial and regional languages with a multitude of local dialects.

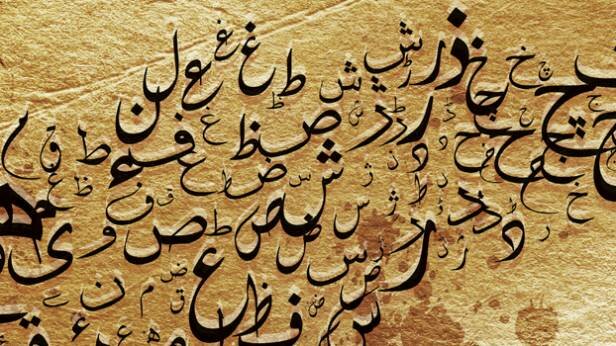

Many of these dialects are yet to be formally categorized, most of these languages don’t have a suitable alphabet or script to write in. They try to use some generic form of the Arabic alphabet and Nastaliq script that Urdu is written in. Urdu itself is historically an independent language to both the alphabet and the script, having existed in oral form under different names for much longer. Urdu is mother tongue to only 8% of the population, English is mother tongue to almost none of the population; the fight of literacy then is also the fight of script, alphabet and language. It is the fight of learning things that don’t come naturally to our native population.

This lack of natural progression from speaking to reading and writing in this country, became apparent to me when I first started teaching adult literacy classes. A fifty year old student of mine, a woman called Naseem Bibi, felt the desire to empower herself at middle-age, she wanted to read and write.

In a few weeks, her desire was turning into frustration. The difference alphabets that can make similar sounds were confusing her. The shapes and forms of the letters were alien to her. She had never heard of or used some of the words that were necessary to learn the rules of the language. The lack of an organic progress from her mother tongue to the written word was seriously impeding her learning.

The experience isn’t too different at the primary school level. Children come from all sorts of linguistic and ethnic backgrounds and often have no rooting in the written languages they’re about to study. Most don’t manage to learn properly before they drop out due to financial pressures.

My own students are frequently unable to differentiate between the ‘tay’ and ‘toay’ sounds, conflating and confusing the alphabets; nor do they think it important to do so, since they don’t need to in their practical lives, it’s only in reading and writing that discerning every alphabet’s sound becomes important.

They have similar problems with ‘qaaf’ and ‘kaaf’, ‘duad’ and ‘daal,’ they don’t understand which ‘hay’ goes where, or what the difference between one ‘yay’ and the other is. The Urdu alphabet and script seem dense and inaccessible to them. Even those who do become proficient struggle to decipher the calligraphic jumbles that are Urdu newspapers.

So perhaps what’s needed along with a bigger emphasis on education is language reform.

In a world that is migrating online we don’t even have a word for the virtual world in our native languages. Nastaliq was notoriously difficult to typeset, it was meant to be calligraphic, hand written.

Because of the problems of font and typeset the presence of Nastaliq online does not match the number of people who can read and write Urdu. Similarly, text messages, e-mails, social media, online chats are all inundated with local language communication in Roman English alphabet, because one script is readily available and the other isn’t.

When both the alphabet and script are facing unpopularity and disuse it’s time, I believe, to sit down and reassess them. Many languages have undergone deliberate reform, Indonesian, Malay, Chinese, Dutch, German, French; the case we are most familiar with however is the language reform in Turkey, when in 1928 a new alphabet was introduced by a Turkish Language Commission at the instigation of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

Although the introduction of a new alphabet had more to do with other social reform and less with literacy, the Romanization of the language brought discernable practical benefits, ease of learning, easier integration with modern teaching method, modern ideas, easier to print, read and publish. The result bears out this argument since following its language reform the literacy rate in Turkey rose from a low 9% to 33% in just ten years.

Imagine what we could accomplish with a 20% rise in literacy rates and ease of teaching and communicating modern ideas. Imagine the benefit to our local languages if they could all be written in a suitable script and easily printed or put online. Imagine the benefit to children who could learn to read English by learning to read Urdu, and vice versa. Imagine the benefit to children of just studying a non-confusing, easier alphabet.

Not to say, of course, that Romanizing our national language is the one and only way forward, this is just an example, out of many possible reforms. Languages that don’t adapt tend to die out and become things of archaic interest only for linguists and anthropologists; Urdu has always been an adaptive language, all it needs right now is to be pointed in the right direction.

The writer is a journalist based in Lahore. She tweets @RabiaAhmed4